Dmytro Putiata, Andrii Karbivnychyi, Vasyl Rudyka

On 21 February 2014, the day after the shooting on Instytutska Street, Russian TV channel Den’-TV aired a story pointedly titled “How to Divide Ukraine.” Den’-TV is a news channel which offers airtime to Russian political scientists and conservative ideologists—Eurasists, Stalinists and Orthodox traditionalists—including Dugin, Prokhanov, and Dushenov. Speaking about the division of Ukraine was owner of Den’-TV Alexander Borodai, little heard of by the public at the time. Few people knew Borodai as a political scientist and PR counsellor, who had worked in Prokhanov’s newspaper Zavtra, a military correspondent, an expert in ethnic conflicts, and a graduate of the Faculty of Philosophy of Moscow State University. There is a funny incident that happened to him as far back as 2002: on July 25th, Russian newspaper APN reported that FSB [Federal Security Service of Russia] Major General Borodai had been appointed FSB deputy director for information policy and special projects, citing sources in the Presidential Administration of Russia. APN went on that the newly appointed officer would deal with “organising FSB’s most sensitive operations in the political field.” Five days after the publication, The Moscow Times called Alexander, who denied the appointment, saying it was someone’s joke for his birthday. APN’s report mentioned the candidate was 35 years old whereas Borodai himself said he was 30. Given that Ukrainian intelligence services do not confirm Borodai’s service in the FSB, there are no grounds for considering it anything but a joke.

Back to Den’-TV’s story, though. The video, apparently, was shot before the tragic events of February 20th, because it only refers to the clashes near the Verkhovna Rada [Parliament of Ukraine], in the Mariinskyi Park, on February 18th. But even without knowing about the turning point that was only about to come, Borodai already speaks of the need for Ukraine’s division. He argues that the developments have demonstrated that Yanukovych is a morally and intellectually weak leader, and Russia cannot bet on him. Borodai assesses regional sentiments in Ukraine: according to him, the West is focused on the EU; the Center with Kyiv is a “marsh” that will take a wait-and-see position and watch what will become of it; and the South and East are oriented towards Russia. He offers Russian national and patriotic circles a new viewpoint on the situation in Ukraine and a proposal for its solution: Do not support not only Yanukovych, but also any of the future Ukrainian presidents—they, so to speak, will naturally focus on the EU. This is explained by the “oligarchic nature of power in Ukraine,” which is not balanced by the “vertical power”—a bureaucratic apparatus, as in Russia. Thus, he proposes that the very idea of cooperation with Ukraine as a political actor be rejected, whereas its territory, infrastructure and population be considered exclusively as resources for strengthening Russia. The southern and eastern regions of Ukraine, his proposal goes, must “somehow” be returned to Russia. He is aware of the legal complexity in terms of international law and the likely consequences of such an action that will be condemned by the international community, yet argues that this will be achieved, at least on certain conditions or by means of certain agreements, by fair means or foul.

This video would not have mattered if it had just been a reflection of the average Russian political scientist, although history would later show that Borodai would play a significant role in spreading Russian influence in Ukraine, having become the first prime minister of the puppet “DNR” [Donetsk People’s Republic] in May 2014 . The story is significant because it fixed certain ideas in time, albeit superficially, which had been born before—and had influential patrons. We shall have a look at Borodai’s chef, whose name is Konstantin Malofeev.

Putin’s Soros

Konstantin Malofeev was dubbed “Putin’s Soros” by Bloomberg. George Soros is a philanthropist and benefactor, known for his support of institutions that promote the establishment of an open society based on the principles of respect for human rights in more than 100 countries. However, modern Russia is not the West, and its patrons support not the development of rights and freedoms but the establishment of the “Russian world” in other countries. Malofeev itself comes from a Soviet elite family that, despite the Iron Curtain, entertained British scientists at their place, with Konstantin himself studying in the United States through an exchange programme. Later on, Malofeev worked in investment banking, earning a fortune due to financial fraud in several high-profile cases. Malofeev calls himself a convinced Russian monarchist, and Ukraine an artificial formation on the ruins of the Russian Empire. It is worth dwelling on a few aspects of his financial activity in order to understand his relationship with the Russian authorities.

In 2004—2010, Malofeev’s company, Marshall Capital, pulled off several financial fraud cases, not least due to Malofeev’s friendship with Russia’s Minister of Communications, Igor Shchegolev, and Sergei Ivanov Jr., the son of Sergei Ivanov, an FSB [Federal Security Service of Russia] general, former Defence Minister, and Head of the Presidential Administration in 2014. In 2007, Malofeev took a big loan in the state bank VTB, which he was not going to return. And, in 2008—2010, he was actively buying up shares at Shchegolev’s prompts, of which only the latter’s Ministry knew that they would rise in price after the planned reform. By 2011, the shares bought by Malofeev for $500—700mln had risen in price to $1.1bln after the reform.

In 2009, VTB took Malofeev to court in London over an unrecovered loan of $225mln. The court blocked Malofeev’s foreign assets. In 2012, a criminal case was initiated against him in Russia over “fraud”—the unrecovered loan was considered as embezzlement.

Being in such a predicament, in the same year, Malofeev sharply increased charity donations through his fund named after St. Basil the Great: the 2012 budget of the fund reached almost RUB1.2bln, making it one of the largest charitable organizations in Russia. Among other things, the fund organises the exhibition “Gifts of the Magi”—Orthodox relics were brought from Afon to Russia, Ukraine and Belarus for the pilgrimage of believers.

An Analytical Note

At the height of Euromaidan, relics from the exhibition “Gifts of the Magi” were brought from Afon to Kyiv. The exhibition was held on January 24 through 30, right at the height of the clashes in Hrushevskyi St. They broke out on January 19th as a response to a package of laws adopted by the Verkhovna Rada with all possible violations on January 16th. The laws severely restricted civil rights and freedoms, providing for measures as absurd as prohibiting to protect the head at rallies. In late January, there were the first casualties; tyres were burning in the downtown day and night; tense anxiety and the shock at the events in Kyiv were literally in the air. And it is at that time when the exhibition arrived, accompanied personally by Malofeev, Dmitry Sablin, and their entourage, which included, in particular, Igor Girkin, a retired FSB officer, then head of the security service at Marshall Capital. He had arrived in Kyiv in advance, on January 22nd, to escort the exhibition.

At the time, according to Girkin, he visited Maidan, where he spoke with protesters. Collection of information took more than a week.

After Kyiv, it was suddenly decided that “Gifts of the Magi” be brought in Crimea. The delegation flew by plane, but in Kyiv it became known that the plane would not be able to sit in Simferopol due to weather conditions. It was arranged with the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine through Anatolii Mohyliov, the Head of the Crimean Council of Ministers, that the plane would land at a military airfield in Belbek. The exhibition stayed there until February 2nd, with two days in Simferopol, and a day in Sevastopol. At the same time, Malofeev and Girkin tried to clarify the situation in the region. Sablin and Malofeev met with Rustam Temiralhiev, Deputy Prime Minister of Crimea, Vladimir Konstantinov, Chairman of Crimean Parliament , and Sergey Aksionov, an acquaintance of Malofeev, then little-known leader of the Russkoye Yedinstvo (The Russian Unity) party, which got only 4% of votes in Crimea in the last election. Less than a month later, during the annexation of Crimea in February 2014, Borodai would serve as the “Minister of Propaganda”—Aksyonov’s personal spin doctor, and Girkin would advise Aksyonov on military issues. Borodai himself described the nature of those relations as “personal-state partnership.”

During 4—12 February 2014, an analytical note was sent to the Presidential Administration of the Russian Federation, then headed by retired FSB general Sergey Ivanov. The note contained a few points explaining the situation in Ukraine. It is believed to have been written by Malofeev. Its key points are as follows:

- Yanukovych’s and his cronies’ regime was named bankrupt, and his possible further support by Russia irrational. The power of oligarchs in Ukraine has no counterbalance, such as powerful bureaucratic apparatus in Russia

- Russia must actively intervene in Ukraine’s developments

- At the first stage, Ukrainian regions must strengthen economic cooperation with Russia within the framework of “Euroregions”—agreements on cooperation between the neighbouring regions of two countries

- The need for Ukrainian regions to accede to Russia is explained by a number of arguments: it would guarantee the security of the gas transportation system; improve the demographic situation in Russia at the expense of the inflow of the Ukrainian population; and Russia would also receive powerful enterprises of the military-industrial complex. Taken together, all that must substantially strengthen Russia’s position in Eastern and Central Europe

- Russia must do its utmost to contribute to the creation of an information background for the moral justification for the accession of Ukrainian regions. The proposal was to blame Ukraine’s western regions for separatism and, referring to their conduct, proclaim the sovereignty of regions in the East and South

- Speakers of the eastern and southern regions must submit their demands to the Verkhovna Rada one by one. At the first stage, the regions should demand the simplification of the referendum process and the organisation of referendums on self-determination, and assign the ideology of the “civil war and the split of the country” to Ukraine’s nationalist forces. At the second stage, demands for federalisation—or, more preferably, confederalisation—must be made. At the third stage, there must be a demand that economic agreements be made on the regional level, including on the accession to the Customs Union. Finally, the regions must proclaim “sovereignty” and declare their accession to Russia

- In order to communicate the idea of referendums on self-determination, local leaders are invited to Moscow for warrants and support. The note mentions the recommended individuals, such as Dobkin, Konstantinov, and Aksenov

- Russia must establish the referendum process. Particular attention should be paid to persuading the world community of the legitimacy and fairness of referendums

- Russia must ensure the widest possible media coverage of these events. Airtime must be given to ideas and manifestos justifying separatism not only in eastern but also in western Ukraine

It should be noted that the announced plan of action was proposed when Yanukovych was still the President of Ukraine.

Wheels Begin to Move

At the end of February 2014, Russian troops began a large-scale redeployment in Russia as part of an unexpected exercise, heading to the Ukrainian border, and occupied strategic sites in Crimea. On the political field, the Presidential Administration of the Russian Federation got into the act. Russia followed very closely the plan set forth in the analytical note, though significant adjustments were made by the fact that Yanukovych had left Ukraine and the Verkhovna Rada had removed him from the post of President. Now Russia had the opportunity to speculate on the theme of the alleged “armed coup d’etat.”

On 27 February 2014, just as Russian troops in the Crimea began the open phase of their operation, VTB announced that it was intent on withdrawing its claims to Malofeev. Later, in 2015, VTB would finally agree on Malofeev compensating around $100mln. The bank did not explain the reasons that made it forgive 83% of the debt, or $596mln at the time, but a source close to the businessman explained that it had to do with Malofeev’s “civic position” about events in Ukraine.

From telephone conversations intercepted by the SBU’s [Security Service of Ukraine], we know of some episodes of the work of Russia’s Presidential Administration. On 27 February 2014, Sergey Glazyev, Advisor to the Russian President, talked with Konstantin Zatulin (Director of the CIS [Commonwealth of Independent States] Countries Institute) about organizing mass rallies in Ukraine. Zatulin mentioned two regions, where everything was ready for demonstrations, namely Odesa and Kharkiv, as well as the organizations to be behind them—Odesskaya Druzhyna and Oplot, respectively. On the same day, Glazyev confirmed in a phone conversation with an Oplot member that the issue of their financing had been referred to the person responsible.

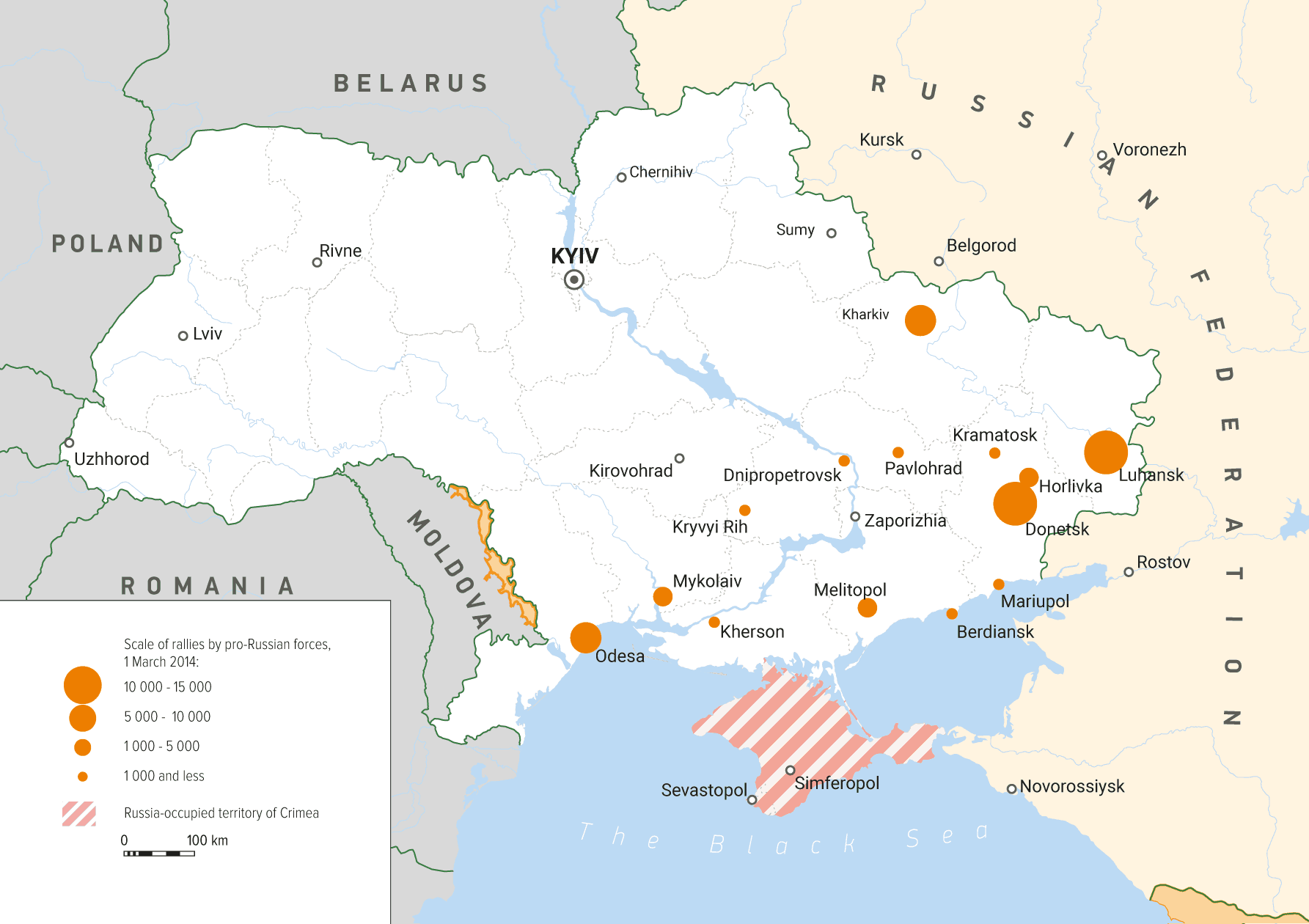

On 1 March 2014, on Saturday, demonstrations simultaneously took place in Ukraine’s regional centers, including Kharkiv, Donetsk, Odesa, Luhansk, Kherson, Mykolaiv, and Dnipropetrovsk, and the large cities of Mariupol and Melitopol. The demonstrators were chanting different slogans—either highly reactional, condemning Maidan; or abstract and ideological, against “fascism”; or various political, ranging from the moderate ones on the expansion of rights and powers in the regions to uncompromisingly pro-Russian ones, calling for seceding from Ukraine and acceding to Russia. The protesters were roused by the appearance of troops without insignia in Crimea and the news of the “permission” from the Federation Council for Putin to deploy troops in Ukraine. On that day, the most radical rally managed to seize buildings of regional state administrations and hang Russian flags in Kharkiv, Donetsk and Luhansk.

In Kharkiv, “tourists” came by buses from Russia’s Belgorod region: It was reported that there were about 2,000 of them. They together with Oplot stormed the regional state administration building, forced Ukrainian activists out of it, poured them with brilliant green paint and beat them through a “corridor of shame.” Russian “tourists” drove back to Russia the same day after the task. The identification of the man who raised the Russian flag over the administration building made for a small sensation: he also turned out to be a Russian citizen.

The events of March 1st in Donetsk were well documented by journalist Andriy Shokotko in his article. The city hosted two large rallies at the same time: near the administration building and on Lenin Square. Images from the rallies might have upset some Ukrainian: there were really a lot of people on the square, with Russian flags waving everywhere. However, the interpretation of those images as radically pro-Russian moods of the demonstrators in the Ukrainian and Russian news media was extremely misleading. The overwhelming majority of them were state employees, whose attendance at the rally People’s Deputy Mykola Levchenko was responsible for. Their chants and posters were a far cry from separatism: They condemned the so-called “radicals of the Maidan” and had to support the stated demands for the independent use of the regional budget, and the general call to Kyiv to “hear Donbas.” But the initiative of the mass rally of thousands was taken away by several hundred organised men. Most of them were brought from Russia, something which they did not even consider necessary to conceal. They held Russian flags, roused participants with pro-Russian slogans, later captured the podium and gave the floor to Pavel Gubarev. Gubarev is a native of the Donetsk region, who worked as a spin doctor from time to time; in his youth he was a member of Russkoye Natsyonalnoye Yedinstvo (The Russian National Unity), a neo-Nazi party; in early March 2014, he was 30. After taking the floor, Gubarev called himself the commander of the “People’s Militia of Donbas” and announced his arguments, consulting his notes from time to time:

- A coup d’état has taken place in Ukraine, and the supreme power is illegitimate

- The country is on the verge of a civil war, and the blame is on Maidan protesters and the oligarchic authorities; the common people of Donbas are opposed to war

- The current Donetsk authorities “made a deal with Kyiv,” so they must be overthrown

- A new governor with broad powers must be elected

- The authorities must swear allegiance to the new people’s authorities

- Donetsk must stop allocations to the central budget

- The Russian Consulate in Donetsk must be opened, where Russian passports will be issued

- He called for a referendum to answer the question of whether Donetsk will remain in Ukraine or accede to Russia

A man from the stage immediately offered Gubarev the post of the “people’s governor of Donbas,” which was met with cheers from the crowd.

Soon, pro-Russian activists from Lenin Square came to the administration building. Inside, several pro-Russian radicals managed to break through and the Russian flag was raised over the administration. However, the meeting of the regional council did not take place, and no political decisions were made. Then mayor of Donetsk Oleksandr Lukianchenko was under the administration, but pointedly chose a cautious strategy amid increasing tensions: he calmed the protesters, carefully maneuvered, avoiding delicate topics, carefully weighing his words, and promised to convene the council only in a day or two, despite the demands of pro-Russian activists that it be assembled immediately.

Local observers Anton Shvets and Ihor Shchedrin recalled that Gubarev’s group had 300 to 400 people, and their activity was considered independent, autonomous, and organized at the personal initiative of Gubarev. At least, local sources indicated that Gubarev’s actions had not been coordinated with the local establishment or influential politicians from Party of Regions. And so it was: Gubarev did not coordinate his actions with local authorities. In 2016, he spoke of regional elites and support from abroad, answering a question about the opportunity to repeat the Donetsk scenario in Odesa:

“I can say one thing – both here and there you cannot count on regional and municipal elites. We analysed and concluded that we could not draw on elites of the occupied Novorossiya; that will not work. Support will be organised in the same way: support of the wide public and the attraction of an organising force from the outside.”

With the “external force,” Gubarev made an ill-disguised hint at Russia. In 2014, Gubarev spoke literally with the words of Borodai about Yanukovych:

“We do not support [Yanukovych] as a political figure, but we cannot deny that he is a legitimate president.”

Therefore, complete lack of communication with the former power centers in Donetsk; the rejection of the idea of cooperation with them; uncompromising pro-Russian rhetoric, translating into pure Russian nationalism—all this is a practical embodiment of the arguments that Boroday announced on Den’-TV channel and which were set out at length in the analytical note attributed to Malofeev.

We shall once more refer to the intercepted phone conversations of the Russian Presidential Administration on March 1st, which make it possible to understand the involvement of the Russian authorities in the events of the early spring of 2014.

On March 1st, Glazyev spoke with Kirill Frolov, an organiser of rallies in Odessa. Frolov—a Russian citizen, a bishop of the Russian Orthodox Church, an analyst at the CIS Countries Institute, an assistant of Surkov and Glazyev—was deported from Ukraine in 2006 for two years by the SBU for inciting hatred and propagating separatist sentiments. In the conversation, Glazyev provided instructions: the administration must be seized, and local MPs need to be convened at all costs; those who refuse must be called “traitors, Banderites and Fascists”, and those undecided forced to come. The similar plan had already been implemented in Crimea, where local deputies were literally forced, under the supervision of Igor Girkin, to come to the parliamentary meeting to vote on the “referendum.” Glazyev gave further instructions: after the deputies in the seized administration have gathered, they will have to adopt a decree on the non-recognition of the Kyiv authorities and request Putin to deploy troops. He gave an example of how regional administrations had been seized in Kharkiv and Donetsk.

That day, Glazyev held another conversation with one of the performers, pressing the latter to tell him about the situation in Zaporizhzhia. It was planned to attract 1,500 people in the city, including “Cossacks,” who would demand from Russia “protection from Banderites.” He appealed to “specially trained people” who would have to beat the Ukrainian forces from the administration. Then he literally dictated that after that, the pro-Russian forces should gather the regional council, form an executive body, confer powers on that body and re-subordinate the police. It makes sense to provide the whole passage from Glazyev’s extremely revealing speech:

“I have direct instructions from the authorities to raise people in Ukraine. Anywhere we can. We need to take them to the streets and do as in Kharkiv, as an example. And, as soon as possible. Because, you see, the President has already signed the decree, and troops are reported to be moving. Why are they sitting on their hands then? We cannot force it to happen, we use force only to support the people, and nothing more than that. And when there is no people, what kind of support can be there? Tell him it is very serious, it is the matter of the fate of the country, and, accordingly, the war is ongoing.”

Gubarev’s rhetoric at the March 1st rally was a replica of the recommendations from the Presidential Administration of the Russian Federation. The slogans, demands and statements that he proclaimed there were practically a complete synthesis of the analytical note and the adapted demanda that Glazyev told the performers in Ukraine on March 1st. And this is not sheer coincidence. Kirill Fedorov’s hacked email revealed that Gubarev was had been elected by curators from the Presidential Administration as one of the regional leaders, and was accordingly instructed. He was one of those who would implement Malofeev’s plan to create Novorossiya of southern and eastern Ukraine.

Excessive Expectations

Energetic yet unsystematic efforts of the Russian authorities to organize a protest movement in the southern and eastern regions of Ukraine had all the signs that those efforts were being invented, corrected, modified, coordinated, and then implemented almost in real time. Together, they were not able to raise a truly massive wave of popular protests among Ukrainian citizens in the southern east.

On March 2nd, the Ukrainian authorities appointed local influential figures to the governor’s posts. In some regions, the appointed were businessmen and heads of financial and industrial groups: Ihor Kolomoiskyi was appointed as governor in Dnipropetrovsk, and Serhii Taruta in Donetsk. One of the reasons for the transfer of power to the local figures was that they had real power on the ground, and therefore much more opportunities to ensure the maintenance of public order amid significant pro-Russian demonstrations in the regions that began earlier.

On the same day, March 2nd, the regional administration was seized in Luhansk. Leader of Luganskaya Gvardiya (The Lugansk Guard) Alexander Kharitonov gave the council’s deputies a resolution of pro-Russian protesters. The resolution provided for a referendum in the Luhansk region on the secession of Donbas; a request for Putin to send troops to Luhansk; and demands that the new authorities be recognised as illegitimate. The deputies refused to sign the resolution, which triggered an assault on the administration building. The deputies left the building through the backdoor without signing anything. Pro-Russian protesters had summoned them back to the building and forced them to adopt a resolution that supported the idea of all-Ukrainian referendum of federalization, and claimed that Luhansk Council does not recognize the legitimacy of a government newly-assigned by Verkhovna Rada. There were also demands to the Verkhovna Rada: to grant Russian language the status of a state’s second official language, disarm all paramilitary formations, guarantee safety for the inhabitants of all regions and keep supporting previous levels of welfare expenses, grant amnesty to Berkut riot-police officers who suppressed the Euromaidan protests, ban several Ukrainian nationalist political parties and organizations (such as UNA-UNSO, Svoboda, Right Sector, Tryzub), which were accused «of pro-fascist and neo-Nazi nature». There was also a demand «not to ban foreign TV channels in Ukraine», which lobbied the right of Russia as an aggressor to keep their broadcasting in Ukraine under the guise of «censorship prevention». In the case of non-compliance, Luhansk Council «reserved the right to ask for help of the brotherly people of Russian Federation».

The very next day the Luhansk prosecutor’s office claimed that the Luhansk Council had overstepped the boundaries of the law. Prosecutor’s office declared the Luhansk Council deputies’ resolution of March 2nd as illegitimate and urged it to be cancelled. Deputies, who voted for it yesterday, said they’d changed their minds, claiming they were misunderstood and that the adopted resolution was not exactly mandatory.

On March 3, an assault on the Donetsk regional state administration took place again. The events of that day are described in the Ukrainian online news outlet Ostrov: the day began with a meeting of the regional council, where Gubarev was given the floor. He announced a call on Putin to deploy “Russian peacekeeping troops,” and explained to deputies the need to recognize the illegitimacy of the Verkhovna Rada and the Cabinet of Ministers, and to stop the allocations to the budget. Finally, the question of approval of the chairman of the regional council was put to vote, with the candidates including Gubarev himself and Andriy Shyshatsky, appointed on that day from Kyiv. When the majority of the deputies voted in favour of Shyshatsky, Gubarev hysterically stated that the deputies “pushed the region into war.” Then, his people, who had been rallying near the administration building all the time, went on assault, broke into the building and took control of the first two floors and the session hall. Having already occupied the chair in the presidium, Gubarev promised to dismiss every official who would not make an oath to the “people’s authorities.”

The absolutely identical scenario was tried in Odesa on the same day, March 3rd. There was also a meeting of the regional council, and the word was given to the local leader of pro-Russian forces, Anton Davydchenko. He demanded the admission of pro-Russian activists who were under the administration to the session hall, but was refused. Then, the crowd tried to take the administration by force, but it did not succeed. No decisions were made by the regional council on that day.

The Ukrainian intelligence services soon detained leaders of several pro-Russian demonstrations, who worked on instructions from the Russian center. Gubarev was arrested by the SBU on March 6th, with a case initiated against him a few days before relating to three articles of the Criminal Code, including article 110, “infringement on the territorial integrity and inviolability of Ukraine.” On March 13th, Alexander Kharitonov was arrested, who at that time was also proclaimed “people’s governor” of the Luhansk region. He was charged with violating article 109, “violent change or overthrow of the constitutional system or the seizure of state power.” Anton Davydchenko was arrested on March 17th in connection with the violation of article 110.

The hacked email of Kirill Frolov (a bishop of the Russian Orthodox Church and an assistant of Glazyev and Surkov) revealed that, in connection with the detention of Gubarev, on March 6th Odesa Archpriest Andrei Novikov wrote him the following letter:

“They in Donetsk did everything by the Russian instruction, as Sergey Yurievich [Glaziev] told us to do … Are you setting me up for prison? Unless Gubarev is released, I refuse to be involved in the project.”

Novikov had something to beware of: The Kremlin had been transferring money to pro-Russian movements of Odesa through him. The sums transferred reached several hundred thousand dollars and were distributed among several Odesa groups. On April 10th, the SBU called Novikov for questioning and, on the same day, he took the last flight to Moscow.

On March 13th, an unprecedentedly cruel clash during the whole “Russian Spring” took place in Donetsk: members of the pro-Russian rally attacked antiwar rally supporters of the unity of Ukraine. The pro-Ukrainian rally was at first flooded with firecrackers, smoke checkers, eggs and bottles, and then attacked with knives, bats and iron bars. Dmytro Chernyavsky, a native of Donetsk Oblast, a 22-year-old member of the Ukrainian nationalist party Svoboda (Freedom) , died from knife wounds. He became the first to die from the “Russian Spring.” His death was perceived as a signal: Andrii Biletskyi, the future leader of the Azov battalion , would later recall that on that day he understood that the war had begun. During the clashes on the next day, March 14th, which took place in Kharkiv, Biletskyi took part in the defence of the Patriot of Ukraine office in Rymarska Street, which pro-Russian activists tried to assault. Two people were killed in the shooting. Russians, including members of the Night Wolves biker club, and then little-known Arseny Pavlov (soon to become the field commander Motorola), also took part in the assault.

Afterword

Days and weeks passed, but the Russian authorities did not manage to produce at least some tangible result. At the time, their attention was entirely focused on the annexation of Crimea, the blockade of Ukrainian units and ships of the Navy, and attempts by diplomats to whitewash the aggression on the international level. Deputies of Ukraine’s regional councils did not call for the deployment of Russian troops, which supposedly would have justified the invasion. Rallies in major cities in southern and eastern Ukraine became less and less numerous, although did not die out completely. For this reason, the new Ukrainian government was demonised by Russian news media, did not do anything sensational, which could have proven its “demonicity.” Despite the fact that Right Sector will continue to be the embodiment of evil in the imagination of Russian sympathisers, it also did not show any real activity. And, the presidential election campaign was being held in Ukraine. These factors, of course, contributed to the normalisation of the situation.

Read also: Ukraine’s Armed Forces on the Eve of the Conflict

The contents of the article are licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. Copyright exceptions are marked with ©.

The article was prepared with the assistance of the Ministry of Information Policy of Ukraine.

SUPPORT MILITARNYI

Even a single donation or a $1 subscription will help us contnue working and developing. Fund independent military media and have access to credible information.

Роман Приходько

Роман Приходько

Віктор Шолудько

Віктор Шолудько

Андрій Харук

Андрій Харук

Андрій Тарасенко

Андрій Тарасенко

Yann

Yann

СПЖ "Водограй"

СПЖ "Водограй"

ГО "Військова школа "Боривітер"

ГО "Військова школа "Боривітер"

Катерина Шимкевич

Катерина Шимкевич

Олександр Солонько

Олександр Солонько

Андрій Риженко

Андрій Риженко