The Russians increased the number of combat dolphins to protect Sevastopol Bay. According to British intelligence, this was confirmed with satellite images. The Militarnyi wants to remind readers through this article of marine mammals history of use for military purposes and try to assess the effectiveness of such a concept.

Early history

Some sources claim that the concept of using dolphins for naval purposes was initially proposed by Russian entrepreneur Emmanuel Nobel in the late 19th century, but his idea was soon forgotten.

During World War I in 1915, the Main Headquarters of the Russian Empire’s Navy was approached by trainer Vladimir Durov, who proposed using seals to search for sea mines.

An experiment was conducted, and within three months, twenty seals were trained in the Balaklava Bay of Sevastopol and then deployed in the Black Sea.

The animals were trained to locate underwater mines and mark them with buoys, and they performed this task successfully.

However, it was not possible to use the seals in actual combat conditions. Almost all of the trained animals intended for war purposes were poisoned, possibly as an act of sabotage.

There is no further information available regarding other attempts to use marine mammals during World War I.

Crimean combat dolphins in the USSR

In 1965, a secret decree of the Soviet Union’s Council of Ministers and a directive from the Commander-in-Chief of the Soviet Navy No. 802/00970 led to the establishment of the 184th research and experimental base of the Navy in Sevastopol (MUN 13132-K), which later became the Oceanarium research center.

The unit’s personnel were assembled on February 24, 1966. Captain 1st rank Viktor Kalaganov was appointed as the first chief, with Captain 3rd rank Vladimir Bilyaev as his deputy. The founding members of the “Oceanarium” included scientists Gorbachev E.O., Belyaev V.V., Sabitov A.A., Manukhov V.V., Bogdanova L.M., Karandeeva O.G., Protasov V.A., Shurepova G.A., Matisheva S.K., and others.

The primary objective of this military unit was to study the physiological, hydrodynamic, and hydroacoustic characteristics of marine mammals, particularly dolphins inhabiting the Black Sea.

Bottlenose dolphins were utilized as models for developing maritime warfare tools. This research aimed to facilitate the advancement of new shipbuilding technologies for both marine and airborne vehicles.

Scientists investigating the hydrodynamics and physiology of dolphins believed that this endeavor could yield not only traditional knowledge but also pave the way for the creation of faster, more efficient, and quieter ships with enhanced combat capabilities.

As the underwater sabotage forces of hostile nations against the USSR started to evolve, the research base was assigned the additional responsibility of studying and training dolphins for underwater search and mine defense, as well as countering enemy combat divers.

In March 1973, the Navy leadership received a confidential report from the American Naval Base in San Diego, which disclosed that within two years, the Americans had successfully trained a group of dolphins and two killer whales to locate and retrieve sunken combat torpedoes. Similar studies were initiated in Sevastopol.

Since 1975, combat dolphins have been stationed at the entrance to Sevastopol Bay as part of the 102nd PDSS Detachment of the Soviet Black Sea Fleet. Their duties included maintaining round-the-clock surveillance and conducting search operations for sunken objects.

These marine mammals proved highly effective in detecting saboteurs, achieving a success rate of 80%. Their performance was slightly lower during nighttime operations, ranging from 28% to 60% success, but they remained within the coastal enclosure. In open sea conditions, their detection rate approached 100%.

Between 1979 and 1994, dolphins were instrumental in locating underwater objects with a total value of approximately 50 million rubles, surpassing the cost of their upkeep by a significant margin.

Dolphins were deployed in situations where conventional search methods were impractical or ineffective. They excelled at finding objects in challenging conditions, such as complex seabed profiles, limited underwater visibility, shallow waters, and beneath layers of soil and silt.

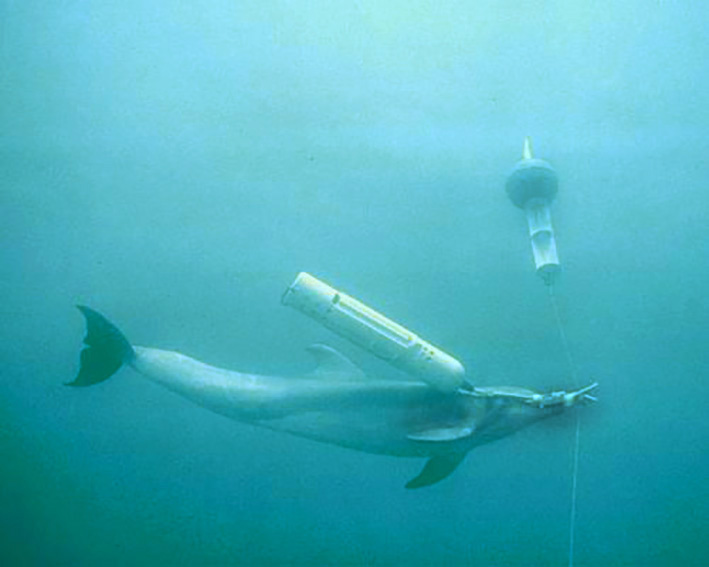

To assist in their tasks, the dolphins wore specialized backpacks equipped with audio beacons and anchored buoys. When locating a lost torpedo, for example, they would swim to it, bury their rostrum in the soil, and release the audio beacon along with the buoy. Divers would then continue the operation.

According to military reports, the establishment and upkeep of the combat dolphin service in Sevastopol proved to be a worthwhile investment within a few years.

Each training torpedo had an approximate value of 200 thousand Soviet rubles, and the dolphins successfully located and retrieved hundreds of these torpedoes.

Mammals have even mastered the art of underwater photography. A specially designed camera was developed for the animals, capable of withstanding pressure at depths of over 100 meters. Dolphins were trained to aim the lens at the target, remain still, and only then trigger the shutter.

The challenge with underwater photography was the use of a powerful flash that could blind the dolphins. Therefore, they had to be taught to close their eyes during the process. By analyzing the photos, it became easier to determine the nature of the objects lying at the seabed and whether it was worth the expense to retrieve them.

Furthermore, the trained dolphins were capable of detecting disguised and acoustically transparent objects.

The search capabilities of dolphins generated the greatest interest among experts, and it was through their search efforts that the military unit gained fame.

In addition to their military duties, combat dolphins were also utilized for archaeological research. They played a crucial role in the search for sunken ancient ships and the retrieval of objects from the seabed.

State Oceanarium Research Center of the Armed Forces of Ukraine

In 1992, the Oceanarium was relocated to Ukraine, where it was commissioned by the Armed Forces to develop the organizational and technical aspects of search and rescue support for all branches of the Ukrainian Armed Forces in maritime and water basin operations.

Most military experiments involving animals were halted almost immediately and only partially resumed in 2012. These efforts focused on addressing the challenges of rescuing sailors, pilots, submariners, and divers, conducting underwater technical operations, and lifting ships.

On February 23, 1993, the Oceanarium became a branch of the Central Research Institute of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine.

On May 16, 1994, the Oceanarium was officially granted state status and underwent reorganization as the State Oceanarium Research Center, affiliated with both the Ministry of Defense and the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. It became a branch of the Central Research Institute of the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

On April 12, 2002, a separate institution called the Research Center of the Armed Forces of Ukraine “State Oceanarium” was established.

The State Oceanarium was under the authority of the head of the Military Scientific Department, who served as the Deputy Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine responsible for scientific work.

By the decree of the President of Ukraine dated November 9, 1998, the territory of the “State Oceanarium” in Kozacha Bay was designated as a zoological reserve of national importance called “Kozacha Bay.”

The “Oceanarium” focused on conducting research on underwater biotechnical systems and developing technical equipment based on bionic principles. These technologies were intended to support underwater search and technical operations involving biotechnical systems, divers, and underwater vehicles.

The institution provided training for animal trainers, divers, and search and rescue personnel.

Furthermore, the research center was involved in applied ecology, environmental monitoring, and certification of ships, vessels, and coastal facilities.

The “Oceanarium” also participated in biodiversity conservation efforts and contributed to the development of water filtration methods and “dolphin therapy” for rehabilitation purposes.

Resumption of training of combat dolphins of Ukraine

In 2013, it was reported by Militarnyi that the Ukrainian Navy had initiated training programs for dolphins using new methods.

According to the report, a group of ten dolphins was being trained for specific tasks in support of the Ukrainian Navy. Training exercises were conducted in the waters of Sevastopol with a focus on underwater object detection and retrieval.

The article further explained that the new training methods primarily targeted underwater search operations. It mentioned the development of advanced active sensors designed to monitor the dolphins’ underwater actions and provide them with commands.

There were speculations that the dolphins could potentially be employed to counter combat swimmers and vessels. However, the Navy Command did not provide any comments on this report at that time.

Additionally, in 2013, there were media reports suggesting that three armed dolphins had escaped from the State Oceanarium. The information was anonymously circulated via email to various Crimean media outlets, and some of them published it.

Nevertheless, the Navy Command denied the accuracy of this information.

Annexation of Crimea

On March 17, 2014, the State Oceanarium was seized by Russian Armed Forces soldiers and local illegal groups.

Only nine loyal sworn servicemen relocated to the new unit location in the city of Odesa. The vessels “Pochayiv” and “Kamenka,” which were owned by the State Oceanarium, came under the control of the Ukrainian Navy.

Currently, the Research Center is situated within the premises of the “Odesa Project Institute” under the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine.

Its primary objective is to conduct research on various aspects, including the development, enhancement, and further utilization of search and rescue equipment, biotechnical means and systems, deep-sea operations and lifting work, military-scientific and scientific-technical support for their advancement, medical-biological aspects of human and animal life in marine environments, general biology, hydrodynamics, and hydroacoustics. Furthermore, the center focuses on studying the behavior, mental activities, and physiological characteristics of marine mammals, as well as establishing scientific foundations for the sustainable use of Ukraine’s marine resources and mitigating the negative impacts of human activities on the marine environment.

The research center is also actively involved in providing psychological rehabilitation to military personnel from the Joint Forces Operation Zone who have experienced post-traumatic stress disorder.

U.S. combat dolphins

The United States actively conducted experiments on the use of marine mammals for military purposes.

In 1960, the United States Navy purchased the first Pacific white-sided dolphin from the Los Angeles Dolphinarium, specifically for the Navy Pacific Research Center in San Diego.

To study the capabilities of marine mammals, a program known as the U.S. Navy Marine Mammal Program (NMMP) was established.

The Naval Biological Station at Mugu Bay (Point Mugu Base, California) served as the research base. In July 1962, the first three dolphins were transported there.

A laboratory was subsequently established on the Hawaiian island of Oahu, in Kaneohe Bay. The research focused on search and rescue operations, mine countermeasures, sabotage, and anti-diversion tactics. The Marine Fauna Study Department of the Pacific Center was responsible for these endeavors.

In 1965, during the SEALAB-2 experiment conducted by the US Navy, trained dolphins were involved in practicing rescue techniques for scuba divers and assisting with underwater work.

In 1967, the Point Mugu laboratory was relocated to the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center Pacific at Point Loma, San Diego.

The United States Navy established five teams comprising sea lions and dolphins. One team specializes in search and rescue operations, three teams focus on detecting sea mines, and the remaining team is dedicated to locating sunken objects.

Combat dolphins were utilized by the U.S. Navy during the Gulf War and the Iraq War, primarily for mine detection missions. Approximately 75 marine mammals were involved in these operations.

In the waters of the port of Umm Qasr alone, dolphins successfully neutralized over 100 mines during the Iraq War.

The U.S. Navy officially denies training marine mammals for the purpose of harming humans or destroying enemy vessels. However, according to certain sources, dolphins were reportedly used against combat swimmers.

During the Vietnam War, specifically during Operation Short Time, a group of six combat dolphins was deployed for 15 months to provide anti-sabotage defense for Naval Base Cam Ranh.

It has been claimed that these combat dolphins successfully neutralized at least 50 enemy combat swimmers during the defense of the base.

Currently, there are five known marine mammal teams comprising a total of at least 75 dolphins and 25 sea lions:

- Mk.4 Mod.0 unit: Dolphins trained for the search and destruction of sea anchor mines as part of rapid response forces.

- Mk.5 Mod.1 unit: (SLSWIDS, Sea Lion Shallow Water Intruder Detection System): Two teams of four sea lions, each specializing in detecting combat swimmers. In addition to their main tasks, sea lions are also trained to search for and neutralize explosive objects.

- Mk.6 Mod.1 unit: (ASDS, Anti-Swimmer Dolphin System): A division of dolphins assigned to detect combat swimmers and typically tasked with guarding important facilities.

- Mk.7 Mod.1 unit: (DSWMCDS, Deep/Shallow Water Mine Countermeasures Dolphin System): Dolphins trained to operate in deep and shallow water areas for the purpose of searching for and destroying sea mines.

- Mk.8 unit: (MCDS, Mine Countermeasures Dolphin System): Dolphins specialized in the search and destruction of sea mines.

Experiments were conducted not only with dolphins and sea lions but also with seals, elephant seals, fur seals, cetaceans such as beluga whales and killer whales, as well as sharks.

Combat dolphins of the Russian Federation

The training of dolphins by the Black Sea Fleet of the Russian Federation is believed to be taking place at the former location of the Scientific Centre of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, the “State Oceanarium.” According to British intelligence, the Russian fleet is also utilizing beluga whales and seals in Arctic waters.

In 2022, satellite imagery revealed the presence of dolphin enclosures at the entrance of Sevastopol Bay. At that time, Naval News reported the presence of 3–4 dolphins in the bay.

Recent images indicate an increase in the number of enclosures, suggesting a larger dolphin population. According to new estimates by Naval News, the bay is now guarded by 6–7 marine mammals.

The animals are designated to protect the bay from Ukrainian combat swimmers and, potentially, drones that could infiltrate the base of the Russian Federation’s Black Sea Fleet.

Conclusion

The effectiveness of using marine mammals in search and rescue operations, object retrieval, and mine disposal is widely acknowledged. These practices have been successfully employed in numerous military conflicts, where trained animals have demonstrated exceptional abilities.

While the use of dolphins against combat swimmers has not been officially confirmed by any country, it can be seen as an effective approach. Without specialized underwater propulsion devices, it would be nearly impossible for a combat swimmer to escape from a dolphin or other marine mammal.

Overall, no individual, regardless of their advanced underwater equipment, can match the capabilities of a trained animal in its natural aquatic environment.

SUPPORT MILITARNYI

Even a single donation or a $1 subscription will help us contnue working and developing. Fund independent military media and have access to credible information.

Роман Приходько

Роман Приходько

Віктор Шолудько

Віктор Шолудько

Андрій Харук

Андрій Харук

Андрій Тарасенко

Андрій Тарасенко

Yann

Yann

СПЖ "Водограй"

СПЖ "Водограй"

ГО "Військова школа "Боривітер"

ГО "Військова школа "Боривітер"

Катерина Шимкевич

Катерина Шимкевич

Олександр Солонько

Олександр Солонько

Андрій Риженко

Андрій Риженко