The Only Easy Day was Yesterday. Hostomel. “Omega”

An interview with a serviceman of the Omega Special Unit of the National Guard of Ukraine about the defense of the Kyiv region in the Russian-Ukrainian war by the National Information Portal Tysk.

Serhiy Haraluzhiy, Mykyta Korobochkin, Yevhen Motolyhin, Dmytro Temchenko, Serhiy Veselukha, and Mortis Aeterna interviewed the National Guard serviceman and contributed to the writing of this article.

. . .

In memoriam of our fallen brother, Vyacheslav ‘Hryvas’ Bashta.

. . .

Hello! Could you please introduce yourself to the readers of our website?

Hi! I won’t specify a unit or its number. I am a senior lieutenant of the National Guard of Ukraine, serving in the “Omega” Special Operations Unit. I joined the armed forces in 2016.

What was the level of awareness regarding the enemy’s plans? Did you have any prior knowledge of the upcoming air assault, and if so, were you prepared for it?

The National Guard’s preparations for counter-airborne assault actions began approximately 1.5 months before the war, including the Zametil-2022 joint exercise. The exercises were aimed at repelling an airborne assault by the most probable enemy (well, it is clear who we are talking about). Therefore, the HQ was aware of the presumable tactical air assault operations at four airfields in Kyiv, including the Hostomel Airport, and preparations were made.

An anti-aircraft missile platoon of the 4th Rapid Reaction Brigade, named after Serhii Mikhalchuk (UIN 3018) was stationed at the Hostomel Airport. This platoon had two more ZU-23-2 (a Soviet towed 23×152mm anti-aircraft twin-barreled autocannon) units at its disposal. Additionally, the 1st Rapid Response Brigade (UIN 3027) designated several units for the protection of the Kyiv suburb airfields: Chayka and Zhulyany. Those units were platoon level and lower; they were reinforced with two ZU-23-2 units and Igla man-portable air-defense systems, along with a number of vehicles (mainly the Varta Armored Personnel Carriers) and trucks (two- and three-axle KRAZ trucks).

Our unit trained to repel a helicopter-borne assault force. However, we learned about the landing at the Hostomel Airport only on February 24, 2022, because the intel, including information for the officers, was received in a very limited and dosed manner.

What preparations were made concerning the invasion from Belarusian territory? Were there any engineering preparations in the north of the region, any minefields placed?

Literally a month before the invasion, the enemy was already conducting an engineer reconnaissance along the mouth of the Pripyat River, starting from the city of Chornobyl and ending with the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant impoundment. That was a sort of ‘line of interest.’ Most likely, pontoons were being prepared in case bridges were destroyed.

Our reconnaissance divisions often traced such engineering vehicles as PMP Floating bridges and wheeled vehicles with pontoons. As well as anchors, because the Pripyat River is rather fast with a swift current, and it’s difficult to deploy pontoons there. We also noticed the increased activity of UAVs and subversive-reconnaissance units. Before the invasion, on February 22, the forward checkpoint of the border guards withdrew from their positions and retreated, splitting into the following directions: Benivka (village in the Ivankiv district of the Kyiv region), Vilcha (Polissya region), and Chornobyl, because the enemy had concentrated quite large forces from all three directions.

Approximately 30 Battalion Tactical Groups were attacking from that direction [Belarus]. That means the total number of enemies advancing towards Kyiv didn’t exceed 20 thousand. Field hospitals were being deployed, logistics infrastructure was being prepared, and the airport in Baranovichi was fully ready for the landing of many IL-76 transport aircraft and rapid unloading. I.e., there was enough personnel and a sufficient number of transport vehicles (two-axle, three-axle, KAMAZ, and MAZ vehicles) to ensure the completion of logistical tasks. That is, everything was working for the invasion forces’ logistics in the Kyiv region.

The engineering preparations in the north [of Ukraine] consisted of setting up local outposts and installing minefields in some areas, mainly anti-tank and anti-personnel, and mixed types of mine-explosive barriers. All of them were installed within a relatively short period of time. In addition, the explosives were also placed on two bridges: the railway bridge, leading to Pripyat from the northern [Belarusian] bank, and the road bridge, located near Chornobyl. All of these bridges had explosive charges on them, but unfortunately, they failed to detonate in time.

So, when I mentioned ‘local fortifications,’ I meant that at that time there were no full-fledged company battle positions and platoon strongpoints, any kind of dugouts, trenches, or caponiers. In other words, no fortifications in the classical sense were created. Basically, such an approach was due to the general plan of potential combat operations, which was practiced at the joint exercise in 2018. In general, the defense of Kyiv was planned out, and paid off. But like in any plan, unpredictable processes that were very difficult to anticipate occurred.

What was your reaction to the start of the invasion, and how did your brothers-in-arms react? What atmosphere prevailed among the commanders at the time?

My personal reaction was quite calm, because the war itself, or rather its active phase, was fully expected. Combat operations were not new to me either, because I participated in the Joint Forces Operation (phase of war between April 2018 and February 24, 2022) in the winter of 2021. And, let’s say, the order of things that was formed couldn’t last forever, and in any case, some kind of epilogue to this story had to happen. So it happened in this format.

My colleagues, in general, had similar thoughts on the matter. Everyone was mentally prepared for the war, and everyone was expecting it. There were no people who panicked or had unhealthy emotions about it. Everyone kept a sober mind and understood what they had to do at that moment. There were no lengthy conversations on ‘pros’ or ‘cons’—everyone was just aware of their task, their place, and their role in the coming actions that were now taking place.

The atmosphere among the commanders was perhaps not the best because, in my view, what was on paper slightly differed from the reality that had emerged on February 24. Some staff officers were not quite clear about what was going on; it was a real surprise for them, and, in some way, it affected the speed of decision-making in some units. In general, I would say, the first week was significantly stressful for the command because some officers of the territorial command (the operational command of the Armed Forces) were not seen until the end of the campaign near Kyiv. They showed up after the active combat operations in the territory of the Kyiv region were over. So there is a very ambiguous situation regarding commanders: I can’t say that all of them were stunned, but I also can’t say that all the officers met the beginning of the active phase in their seats either, let’s put it that way.

So concerning the reaction, it was generally all right. There was no demoralization, as Russian telegram channels and the news media heavily reported. Our enemy had quite expectative tactics, and, for the most part, we were ready for the way they were going to act. Therefore, everyone understood everything the way they were supposed to, and, so to speak, no extra words were needed.

Regarding the atmosphere, there was a feeling of some misunderstanding among the active-duty units and a little detachment from what was going on. For example, one of the National Guard units faced a very serious problem on February 24. They received an order to simply go into the forest around their military base and take up a circular defense. That’s all well and good, of course, but the circular defense was organized chaotically and was not centralized. The higher-level commanders did not communicate orders to the tactical-level officers. Some scraps of orders were sent down to battalions and companies rather than complete ones, which ultimately led to their misinterpretation and a couple of very serious mistakes that could have then resulted in serious consequences. But things worked out the way they did, and everything turned out fine.

It’s also worth adding how February 24 began personally for me. On February 22, we arrived from the Zametil-2022 exercises and had a day off. We arrived in the first half of the day, and it took some time to deliver the ammunition, load the equipment, and participate in the debriefing with the detachment command and the Territorial Command. During the debriefing, there were many interesting discussions about the future conflict, or rather, the escalation of the current one.

Most of the people from the Territorial Command, officers with a rank no lower than major, expressed the opinion that the conflict was not going to happen. They seriously persuaded the unit’s personnel that there would be no hostilities on the territory of Kyiv, the Kyiv region, or in general in other parts of our country. Our old-timers who understood the essence of things a little from their own observations and from their friends in other different units involved in counterintelligence, foreign intelligence, etc., started to guess that there was some unhealthy rhetoric to justify the conflict by asserting it wasn’t going to happen.

On February 23, I was recalled from my day off. We spent some time at the base, longer than it was necessary, and then went home as it was the end of the working day. On the evening of February 23, my girlfriend and I went to a movie, and everything was already clear to me: the general atmosphere and general spirit, and some sixth sense was telling me that it would be better if the 23rd had not ended. The next day at 5 a.m., I was informed that a full-scale invasion had begun, so I had to get to my unit by any means necessary.

Why do you think the possibility of the outbreak of a full-scale war was denied at all levels, up to the top leadership of the country?

I think this information was known to a narrow circle of people and was spread in small portions across units, officers, and some line ministries, so it simply could not reach some officials. Perhaps sabotage was employed somewhere, i.e., information deliberately did not reach end users — units at the tactical level or directly to military units. There is quite a lot of speculation on the subject, but to give a definite answer at this point is impossible because there are too many sources and, accordingly, too much contradictory information on the subject.

But personally, my thought remains the same as I mentioned above: firstly, it was dosed information, i.e., it came in limited portions and was incomplete, and that significantly changed the perception of the situation as a whole; secondly, it was a deliberate failure to give information to officials who should have possessed this information because the superiors and commanders weren’t interested in the information getting to third parties; thirdly, in general, it was justified because spreading specific information about the beginning of active combat operations among the military would inevitably be leaked to the civilians and cause panic. As a result of such panic, the enemy would have been able to postpone its plans.

What were the first missiles’ targets? What was done to minimize damage from the first wave of missile strikes? How do you assess the effectiveness of the Russians’ first strike?

The first wave of missile strikes was aimed at the main and rear command posts, and, of course, at known alternate command posts. Their main task was to hit these targets. Further, the missiles were directed against the locations of air defense facilities, i.e., battalions of S-300 anti-aircraft systems. They hit the communication centers and command posts of military units.

The activities to minimize damage consisted of deploying Alternate Command Posts away from the main command posts and redispersed communication and control systems. By the way, we managed to create a fairly effective field and operational network of communications due to Starlinks. Anti-aircraft missile systems were withdrawn from their permanent stations, and the same was true of ammunition, equipment, and weapons in other units. Within 24 or 48 hours, everything was brought to the new rally point as much as possible, and everything was stored there for further use in wartime conditions, for intensive combat.

As for the operations of enemy aircraft, it was used to suppress the radars and, consequently, the air defenses. To do this, they used anti-radiation missiles. The effectiveness of the first strike, of course, was quite mediocre because the enemy had not achieved the main objectives of such a strike: command posts were not taken out of action; the logistics system was not suppressed; and anti-aircraft defense functioned as usual. Overall, the tasks continued to be received and carried out by our units that went on to operate.

I would say that the effectiveness of the first strike was extremely low for a massive, high-precision strike. And in general, I would like to point out that most of the missiles simply didn’t hit their target because they had a huge, really wide Circular Probable Error. Some missiles hit completely the wrong targets; for example, on the territory of the military unit where we were at the beginning of the invasion, a cruise missile, which cost several million dollars, flew right into the summer eatery. Well, I mean, f*ck, of course, it’s a very important target to hit with strategic weapons (laughs), but sh*t happens. So the effectiveness of the missile and bombing strike is assessed as unsatisfactory and extremely low. The task was not accomplished, and, consequently, the enemy faced very fierce resistance.

What were the first actions of the commanders and soldiers in general since the immediate outbreak of war?

Regarding the National Guard units, I can say for sure the following: in Hostomel, the unit that remained at the base was deployed for battle and prepared to defend the airport. Other units were put on combat alert, and, accordingly, groups of the so-called mobile reserve were formed quickly and attached to the units of the Armed Forces, namely the 72nd Brigade. And then the commander of the brigade distributed the units at his discretion.

As for the actions in general, different units had different tasks. For example, Unit 3066 (the 27th Separate Pechersk Brigade of the National Guard) was assigned tasks that were significantly different from those assigned to military Units 3030 (the 25th Brigade of Public Security Protection), 3027, 3018, and 3001 (the Northern Territorial Administration of the National Guard). There were quite a lot of units in Kyiv that belonged to more than just the National Guard.

The tasks were different, and I can’t say what each rank-and-file soldier did, but as for the units that I know of, the tasks were quite common: for example, reinforcing the Armed Forces of Ukraine units in the most breakthrough-dangerous areas. From the beginning of the ground phase, after the airborne assault, the directions of Dymer and, respectively, Kotsyubynske, Irpin, Horenka, Moshchun, and Romanivka were reinforced. That is, potentially dangerous areas where the enemy could put pontoon crossings or organize wading across the river.

As for us, we were carrying out various tasks, and we had no ordinary privates; our unit consisted of sergeants and officers. Our command at that time knew clearly what to do; we were carrying out various special tasks, including special reconnaissance tasks. They were quite extensive, so to explain, we need to go into more details.

Perhaps the command had its own nuances in the organization of combat, and the defense, which resulted in some distraction in the combat orders that were received. For example, the Special Forces were told to hold the line near Obolon with the regular National Guard units and wait for something.

Of course, there was a certain perplexity and a lack of concentration. The pretty mediocre level of organization of actions and management of personnel by some commanders, formed a picture in which few understood how to organize those or other types of tactical maneuvers, tasks, and the order of their implementation.

I mean, tactical-level officers lacked such basic things as the ability to plan the actions of units. Not to mention such complex matters as TLP or MDMP (Troop Leading Procedures and Military Decision Making Process — models of military decision-making according to NATO standards, intended as a planning tool for the primary staff of battalion sized units and larger as opposed to the TLP, which are used to guide units subordinate to battalions). Even such a simple algorithm of decision-making by the commander was missing. For the first 3–4 hours, there was a certain chaos in the actions, resulting in incomprehensible maneuvers. Many people barely understood what they had to do; this concerns regular National Guard units, where there were both conscripts and professional soldiers. The situation was better in units consisting solely of professional soldiers.

What happened in Chornobyl? What unit was stationed there, and what was the fate of the garrison?

The Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant has been guarded by UIN 3041 (1st Separate Battalion for the Protection of Especially Important Facilities – ed.) since the formating of the Internal Troops of Ukraine (predecessor of the of the National Guard of Ukraine – ed.). It is stationed in the town of Slavutych and belongs to the category of military units tasked with protecting critical state facilities.

With Chornobyl, the situation was such that the garrison had no heavy weapons, and since it was just a guard, they had only light firearms (i.e., AK-74) and, possibly, RPK and SVD (Kalashnikov hand-held machine gun and Sniper Rifle, System of Dragunov – ed.). In other words, any anti-tank weapons or heavy weapons were out of the question. The Guard Unit that was there during the assault on the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant was encircled and forced to surrender.

According to the information I received from the officers and servicemen of this unit, who were on guard at that time and managed to avoid capture, two Tiger armored vehicles with Russian Special Operations Forces operators entered the territory of the Nuclear Power Plant. Our soldiers were given an ultimatum: either surrender their weapons immediately or face execution. Since the Guard Unit had no right to leave their posts under any circumstances, the Chornobyl garrison personnel appeared to be the very first prisoners of war in this conflict. If I’m not mistaken, 141 soldiers from UIN 3041 are currently in captivity. I could be mistaken, because I do not remember exact figures, and for me, this information is quite distant, as some parts are very indirectly related. But I do have some information.

We attach the post by Ukrainian paratrooper Vitalii Voz about the beginning of the war in the Chornobyl zone.

How did it all start for me?

23.02 Chornobyl exclusion zone

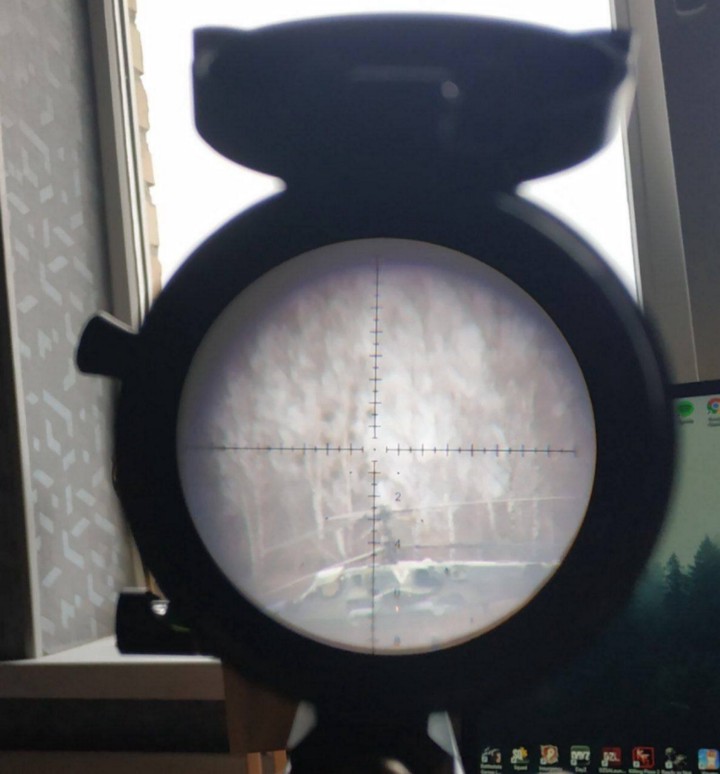

Our HMMWV (on the 1st photo) was fully loaded, starting with 7.62mm rounds for the AK and ending with RPG-22 and 12.7mm ammo for the DShK (heavy machine gun – ed.). In addition, the commander said to load 11 more pieces of TM 62 — a bunch of anti-tank mines. There was no place to put them, and we threw them into the machine gunner’s turret, thinking he could put up with it since it wasn’t far to go.

We checked the fuel level of the HMMWV, confirmed the radios were working, ensured everyone was in position, and made sure we had all necessary equipment such as Night vision devices, thermal imagers, batteries, etc. Our mission was to support the border guards at one of the checkpoints along the Belarus border during nighttime shifts.

To be honest, we did not expect the war to start; we were skeptical. In reality, we thought it was just muscle flexing, a training that would end in a couple of weeks, and we would return to the training ground…

I could not even imagine that in 5 hours I would be ordered to set up this mine barrier and put it in a combat position. That I would have to hear the air-alerts in the cities, artillery shelling from Belarusian territory, shouts on the walkies — everything seemed so unreal…

The state I felt was one of uncertainty about what was happening. It felt like a dream, to some extent, and I experienced a mix of panic and joy. Why joy? Because I had been preparing for this for five years, and I wanted to apply my skills to the fullest.

@ai__karamba was sitting behind the DShK on a humvee, taking a position and shouting to me: “Rudee, we’ve been waiting for this.” We looked at each other and smiled…”

How did the Russians advance in the border zone (Pripyat-Ivankiv)? What units took up defense, how many were there, etc.? What happened to the troops who were defending near Ivankiv? Is it true that they were able to retreat on foot through the forests?

Regarding their advance, it can be said that the main lines of engagement in the Chornobyl district specifically were at Benivka, Vilcha, partially in the Chornobyl, and on the territory of the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant. Units of the 80th Air Assault Brigade, plus UIN 3041, two combat groups of the Omega Special Operations Detachment, and several Border Guard units were present there.

There was no task to deter enemy units in the Chornobyl and Ivankiv areas. There were, of course, tasks to destroy elements of infrastructure, namely bridges: a road bridge and a railway bridge. For unknown reasons, the bridges were not blown up beforehand, although the real reason was that the offensive was expected at one time but in fact happened at another time. That is, the enemy began the offensive earlier than the headquarters had anticipated. In a sense, such an early attack was unexpected for our units.

The enemy initially formed an advance group, i.e., 4-5 Battalion Tactical Groups (I can’t tell the exact number) with tanks, IFVs, Armored Personnel Carriers and BMDs. The BMDs (i.e., airborne units) arrived a little later, and they had to move on foot as the air bridge operation failed. It failed because Hostomel, Vasylkiv, Kyiv Chaika Airfield, and Zhulyany Airport were not secure for airborne operations, or rather for the deployment of military transport planes. This resulted in the landing troops having to move towards Hostomel in ground combat formations.

The enemy attacked in two echelons: the first echelon moved to break through, ignoring and bypassing the main settlements and evading the combating that could delay their advance towards Hostomel. The second echelon was already directly occupying large settlements, engaged in the construction of checkpoints and other fortifications, and so on. In general, it turned out to be a kind of blitzkrieg attempt.

The HQ planned to stretch and disrupt the communications and logistics of the enemy while it had already almost approached Kyiv due to selective strikes on logistics hubs by sabotage groups, Special Operations Forces, and other special operations detachments. I can’t name exactly the units that were on the defensive near Ivankiv because it was a mess there by the time all forces retreated from Chornobyl. However, as to Dymer, there were UIN 3027, 3066, 3030, the 72nd Brigade, “Omega” Special Operations Detachment, and other units of Special Forces such as the 140th Special Operations Center, the Security Service of Ukraine’s Special Group “Alpha”, the KORD (Rapid Operational Response Unit is a special purpose unit of the National Police of Ukraine – ed.) and other distinguished on the battlefield units. There may have been someone else, but I don’t know that.

As for the servicemen who were defending the Ivankiv region, their fate was unenviable. Most of them were taken prisoner, including the garrison of UIN 3041 stationed in Chornobyl. Unfortunately, they were nearly totally captured by the enemy. As of August 2022, the fate of the prisoners of war is unknown due to the lack of communication channels to clarify their status, and as a result, their status remains unconfirmed. One “Omega`s” combat group had to leave on foot as they had to abandon their equipment, which included two Kozak Armored Personnel Carriers, and one MAZ truck. The enemy later employed these vehicles for infiltration reasons.

Can you give more details on the infiltration episode?

During the hostilities in the Chornobyl zone, the “Omega” Special Operations Detachment units left two Kozak armored vehicles and one two-axle KRAZ vehicle there, with the National Guards’ license plates and all the innards. The big problem was that the enemy used these vehicles for their initial infiltration into Kyiv. Those rumors about how Russian special forces were going to kill Zelensky were all true. These groups entered in vehicles that had previously been abandoned by our forces. But fortunately, none of the enemy’s attempts to eliminate anyone from the higher echelons of power were successful. So we have come to the conclusion that the enemy really was in Kyiv, in some of its limited groups, usually Intelligence or Special Forces Units. These groups were either working in the first echelons or had infiltrated through the checkpoints due to the chaos that was going on.

Which units other than the 4th Rapid Reaction Brigade (UIN 3018), 1st Rapid Reaction Brigade (UIN 3027), and “Omega” were involved in the fighting for the airport? Who initially engaged in the first battle, and which unit was the first to arrive there to assist?

Regarding the fighting at Hostomel Airport, it started for me personally at 9 a.m., when we arrived at the base (we are based at, for example, UIN 3027). So we arrived, received the weapons, and drove out the vehicles — we had two Kozaks and one Varta armoured vehicles. And after that, we received the task: we had to move to the Hostomel, and there we had to provide direct combat support to Units 3018, 3027, and Territorial Defense Forces as well as to the 140th Special Operations Center.

Anyway, in fact, there were so many units, and since it is impossible to list them all, everyone was trying to claim fighting for Hostomel Airport for themselves, which is not quite right because it was a complex operation and many units from different military and enforcement agencys were involved. Asserting that the Special Operations Forces carried out the Hostomel battle and the National Guard or conscripts shot down all the helicopters — no, it does not work like that. Regarding defense, there are a lot of people claiming sole participation in the defense of Hostomel Airport. But there were many units involved in the defense of Antonov Airport, and it’s kind of hushed up.

Everything was much more interesting: firstly, the battle itself started when enemy Mi-8 helicopters under the escort of Ka-52 attack helicopters approached the airstrip. Apparently they did not expect any resistance, and the first troops landed on the runway. Accordingly, two of the four helicopters that had landed were destroyed by ZU-23-2 guns that had been deployed just beyond the runway in the direction of Unit 3018’s base, hand-held anti-tank grenade launchers, and small arms fire. There are photos of their wrecks on the web; they were sprawled out on the runway; it was just the very first landing of their assault forces. Almost all of them were doomed and killed; other squads had managed to flee under fire by hiding behind aircraft hangars and being covered by damaged helicopters. The fire was coming from all sides; that is, it was heavy and constant. So the first landing was suppressed and, I would say, defeated.

The first battle was fought by us, “Omega”, then the Units of the 3rd “Irpin” Battalion, air defense platoon, and logistics company of UIN 3018 — those were the first ones who went into battle. Then the more eminent units joined, and let’s say it did not happen in stages — there was no first, second, or third assault. I explained my point above at the end to differentiate the concepts. For a complete picture, we should say that there was no battle stopping, i.e., there was no tactical pause in the battle for Hostomel Airport between the first, second, and third assaults. After the unsuccessful landing on runway, the enemy realized everything and changed tactics. They landed their units near Hostomel, to the north of it, on the edge of the forest, and the paratroopers were already moving out in foot combat formations: chain, diamond-shaped combat formations — so we can’t say they were acting unprofessionally, like some people claim.

The enemy acted in a well-coordinated manner and had air support, which is important because Ka-52s had very serious fire pressure on us during all the battles for Hostomel. This included the firing of unguided rockets, heavy fire with autocannons, and the use of anti-tank guided missiles on our equipment. We lost two combat vehicles during the battle for Hostomel, and they were taken out of action by anti-tank guided missiles outside the line of sight. That is, as soon as the enemy realized it faced organized resistance, their helicopters started operating from behind the forest edges. In other words, playing a kind of ‘catch-up’, they flew behind the undergrowth, appeared from behind the forest, dealt a quick blow, went down, and then chose the next firing position. The enemy acted competently and coherently.

The number one problem that arose during the defense of Hostomel was communication. Unfortunately, National Guard radios operate on high frequencies; we had Motorola and Harris, so in general, we had a mixed type of radio. The Special Operations Forces used Harris’s exclusively, while UIN 3018 and 3027 only used Motorola. There were very serious difficulties with communication, for obvious reasons. And initially, there were friendly fire attempts, but luckily, due to the experience and professionalism of some units, we managed to avoid injuries and casualties among the cooperating units.

The second issue was the shortage of air defense equipment. ZU-23-2 had no ammo and had to be reloaded later due to the conscripts who got ammo boxes from some stash, and anti-aircraft gunners urgently reloaded them. Well, this is ridiculous. The man-portable air-defense systems were only at the disposal of UIN 3018, and to be mentioned, it took time to first find them, then they were brought into fighting position — well, it was hard enough, let’s just say.

https://youtu.be/HE_aCuAQqAo

Towed and self-propelled Anti Aircraft systems — were they on the helicopters route during the landing operation in Hostomel? If so, how did they perform? If not, how were MANPADS used? How effective did they prove to be?

I would further add to the disadvantages the lack of air defense equipment in sufficient quantities. In fact, there was a situation when we left for Hostomel: by some miracle, man-portable air-defense systems were not in our vehicles, and we were told previously that “guys, you shouldn’t take them; everything is there.” This was the first task 200 (unduly risky – ed.) I received during this war; that is, in the first hours of the war, I received task 200, a dumb task that could not be accomplished without these man-portable air-defense systems.

The third problem was that the enemy reached Hostomel Airport very quickly, with minimal casualties along the way. Yes, the AA autocannons were deployed: for example, at Mezhyhyrya, there were several ZU-23-2 squads, and man-portable air-defense system operators were deployed, and for some reason something went wrong, to put it mildly. I cannot say exactly what happened because I was not personally present there and only rumors reached me as it all happened. But in fact, the situation was such that the air defense couldn’t manage to repel the airborne troops to the full extent, i.e., the enemy was not eliminated in volumes sufficient to terminate the operation. So we had what we had: the landing at Hostomel, the first hours of the battle (up to 12 p.m.), and then we got what we had.

If there were ZU-23-2s, they would have torn those helicopters to pieces at such an altitude, most likely if there was a satisfactory density of fire and a sufficient number of anti-aircraft guns. Unfortunately, the exact route was unknown, so there were probably no AAs there. Man-portable air-defense systems were used in Hostomel — to a limited extent, but they were used. In fact, man-portable air-defense systems proved to be quite effective against helicopters, including the Ka-52 attack helicopters. It is quite a good thing for countering low-flying, medium-speed targets, and one of the main lessons of this war is that man-portable air-defense systems must be present in the companies, whatever they may be.

Who was dropped in our territory? What was the fate of the airborne troops?

Well, it is clear that the landing forces belonged to VDV (Russian airborne) units: The 45th Brigade was the main unit that took part in the air assault operation. The enemy had planned to deploy paratroopers from the 45th Brigade onto the runway at Hostomel in order to secure it and its approaches. This would have allowed for the landing of IL-76 aircraft carrying IFVs and units from other airborne brigades that were already prepared for ground operations.

What was their fate? The first landing force was destroyed by approximately 40%, that is, three helicopters were put out of action; they were left lying on the runway as carcasses, plus one Ka-52 was shot down (see the list of confirmed Russian helicopters destroyed in Hostomel – ed.). It was shot down using an Igla MANPADS. We don’t know who the f*ck shot it down because our guys didn’t do it; the conscripts said they don’t know who shot it down, and the 140th Special Operations Center also pretended they didn’t know. And then they were interviewed and said that we shot down the Ka-52 with Igla man-portable air-defense systems. When we came out and were angry about the issue, there was no constructive discussion on it. In any case, there is a fact, glory appropriating is another thing entirely, and I believe it is absolutely irrational now.

As to the fate of the next landing troops: they began acting more professionally; they deployed in battle formations already on foot. On top of that, they suppressed us with fire, supported by their aviation. Around 11 a.m., their field artillery had already started to fire, I don’t know if it was self-propelled or towed. The enemy reached the Dymer borders, which they could not break, but they bypassed our main defense lines and approached Hostomel. Accordingly, by 1 p.m., we were already aware that their armor was coming towards us; there was at least one Battalion Tactical Group on the march, that had broken through after all. I did not count how many tanks there were; I saw two, and that was enough for me, let’s say. We did not have enough anti-tank weapons, i.e., we had no NLAWs or Javelin anti-tank missiles as such, and no Stugna-Ps (Ukrainian anti-tank guided missile systems) either.

Why do you think there were not enough air defense weapons in the potentially endangered areas? What prevented these areas from being reinforced?

The problem is that the senior leadership did not really seriously consider the possibility of carrying out a real air assault operations on critical infrastructure, such as military and civilian airfields, or a dual purpose. Accordingly, this turned out to be such a, I would say, f*cking zany situation when the enemy knew that we were skeptical about such options and hit exactly where we expected, but the hit was not so grave.

But I would add that the units responsible for the Airport were UIN 3027; their staffing was mainly composed of conscripts, and the number of servicemen on contract, i.e., professional military, was minimal. The enemy knew about the real state of things in the units that were responsible for protecting the Airport. They knew that the 4th Rapid Reaction Brigade was on rotation after the Joint Forces Operation, and the enemy was quite well aware of the conditions that had developed by February 24. Additionally, I believe that the enemy’s underestimation was the biggest f*ckup at HQ.

Was there a VDV troops on IL-76’s in Vasylkiv?

Their landing was planned, but it could not happen because the enemy did not occupy the airport with a tactical landing forces and could not secure the landing of the IL-76 military transport aircraft and so on.

But were there some battles, or were our troops fighting with each other?

Yes, there was some hostilities, but it was not paratroopers; it was groups that came in from the side of Brovary city, from the north-eastern flank. The battle for Vasylkiv would have happened if the same trick that was used on Hostomel had been pulled there. This is their tactic in general: they use troop transport helicopters to land assaultmans, drop elite units, secure the runway, and prepare to meet the military transport aircraft. It is a very complicated operation from a tactical and timing point of view. All the logistics and timing issues have to be clearly defined so that there is no delay, because if the ILs are late, then the enemy counterattack will most likely crush the landing troops securing the airfield. Exactly such a situation would have happened in Hostomel if the armored troops from Dymer had not approached.

Can you tell us more about the battles in Vasylkiv?

I do not know the details.

Who destroyed An-225 Mriya, and by what weapon?

Our artillery.

When did the Ukrainian military leave the airfield and the surrounding area?

Units withdrew from Hostomel Airport and the surrounding area by the evening of February 26. The defense was established along the Irpin River, and there were fights in the direction of Bucha and Irpin, i.e., the enemy was breaking through to these settlements to either bypass the Irpin bridge and enter Shevchenko Square or bypass Irpin and jump right out at Kotsyubynske.

In your opinion, what were the main and most gross mistakes made by the Armed Forces of Ukraine and the Russian Armed Forces during those days and in general in the north of the Kyiv region?

For the Russian Armed Forces, the most serious mistake was stretching communications and actually conducting a number of operations, like a tactical landing, which, without proper suppression of air defense, was impossible. This is the first mistake.

The second one was stretching the communication lines from Belarus mainly through the roads, which in addition were poorly controlled and even uncontrolled in some parts. The enemy did not expect a long phase of combat operations to the north of Kyiv. That obviously resulted in a number of logistical problems and additional difficulties created by our Special Operations Forces units and some Territorial Defense Units, who understood what was going on.

The third and most important mistake was underestimating the enemy. They were counting on the Units of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, the National Guard, and other armed formations to flee as soon as they were about to lay siege to Kyiv. But it turned out to be nothing of the sort, and the siege of Kyiv turned out to be quite a serious operational and tactical defeat for the enemy, if not a strategic one.

Another mistake was that the enemy was planning to swiftly capture the bridges. Since there were bridges along the Irpin River, the enemy forces were initially stretched there: from the Irpin town till the Kotsiubynske settlement. All of these bridges were destroyed as soon as they approached them; that is, they stretched along the river, and they did not have pontoon-bridge fleets ready immediately; the first pontoons began to be deployed closer to March. In fact, the enemy got a forced two-week break when the fighting was held on the opposite side of the Irpin River, i.e., where the cities of Irpin, Bucha, and Hostomel were located. Accordingly, the enemy tried to adjust their plans to the current circumstances very quickly but didn’t succeed in doing so.

One more mistake, in my opinion, was the very bad organization of the enemy radio communication, communication between the units (in general, it was our problem too, a mutual problem, I would say). The enemy very often lacked professionalism to coordinate artillery fire; they weren’t capable of reconnoitering the results of artillery shelling or another type of strike. Therefore, they had difficulties destroying our forces; during the Kyiv campaign, Ukraine’s Armed Forces and the National Guard’s losses were quite small, if assessed competently. I mean according to the assessments in the Armed Forces, in the National Guard, and in other armed formations directly, as well as open sources like Oryx.

Our major mistakes in some sense overlap with the Russians’, i.e., we have underestimated them; we have made very big mistakes in timing because we were expecting the enemy on February 23rd, nothing happened on the 23rd, and accordingly what? Everybody relaxed. And on the 24th, everything f*cked up. That’s how unpleasant the situation was.

Communications’ organization was also beyond ideal. In the first days, cooperation was badly organized, so there were very frequent cases of friendly fire, getting hit by our own and enemy artillery shelling, general confusion, and, so to speak, a slow transfer of intelligence data, orders, and combat orders from the HQ or from the higher levels to the bottom. There were situations when the lack of communication and (Starlink terminals (which were not yet available in sufficient quantity) complicated the operational transfer of information. Among the significant problems was that some units were combat-ready de jure, but de facto there was nothing; that concerned more the National Guard Units.

At what point do you think the Russians finally abandoned plans to create the ‘air bridge’?

At the moment, when the first air assault on Hostomel was repelled and the attempted landing on Vasylkiv was stopped.

How would you assess the performance of the self-propelled SAMs, and the S-300 SAMs in particular? At what point did air defense systems like the Osa and Buk start operating on the line of battle?

Without the Buk and S-300 SAMs of various modifications of the Vyshhorod air defense division, it would have been very, very bad, as the enemy would have had complete air superiority and they would have done whatever they wanted. But since the S-300 SAM units were spread out beforehand, the enemy aviation at the beginning could not achieve air superiority or provide support to their landing force in Hostomel. Their combination of Special Forces and aircraft failed.

Osa started operating around February 25, when enemy aviation was operating on the Irpin-Huta-Mezhyhirske line. As far as I know, at that time, the Osa-AKM SAM shot down one of the Mi-8AMTSh helicopters. Buks entered Kyiv somewhere on February 27-28, which almost nullified the enemy aviation’s action thanks to the appearance of the Buk and Osa systems. So, I want to say that the anti-aircraft missile systems, even though they were Soviet-made, played a pretty significant role in repelling air strikes and destroying cruise missiles and other types of weaponry.

How did the Russians manage to get to the outskirts of Kyiv so quickly? What do you attribute it to?

It is simple: they did not stop during the movement, did not unfold the front line, and did not prepare for prolonged battles. And we were bringing their communications and logistics to a halt so that we could use the advantage of firepower. There was no other way.

A couple of words about enemy subversion and reconnaissance groups (SRGs) in cities and the resulting panic. How were the Russian saboteurs operating in reality? As far as I know, Russian saboteurs conducted sniper fire on the National Guard’s military units in the first few days. Can you confirm this?

No. There was no sniper fire; there was a shoot-out at Petrivka with the National Guard’s UIN 3066 (later confirmed as friendly fire), and in the evening on February 25, there was a shoot-out near UIN 3030’s base. That one was the enemy’s fire. Well, there were subversion and reconnaissance groups themselves. Actually, their role is excessively exaggerated. Fear has big eyes, as they say. There were many people who really caused a ruckus, either out of fear or on purpose (they were spreading false information). Therefore, there were Subversion and reconnaissance groups, yes, but not on the scale and in such volumes as they were described.

Did the real saboteurs who were caught belong to any agency? Are you aware of their fates and cases of exchange?

Yes, they were from the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (FIS, commonly known as SVR) and Main Intelligence Directorate (commonly known as GRU). The last major swap of Azov soldiers with Russians was with FIS and SVR saboteurs. And pilots, in addition (this part of the interview was recorded in August – ed.)

Who was, in your opinion, the most worthy opponent?

The 45th Brigade, units of the Directorate “A” of the FSB Special Purpose Center, separate combat groups of various special purpose units. And the artillery.

Russian media sources are spreading the information that the Ukrainian military is allegedly unable to withstand close fire contact and is quickly crumbling. How is this working out in reality on both sides of the conflict?

It varies greatly from unit to unit because there is a very strong difference even between different battalions, companies within the same military unit, brigades, and so on. It is impossible to claim definitively that we are all equally proficient in close combat, just as it is impossible to assert that all units of the Russian army and their counterparts in the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People Republics are also equally skilled in this regard.

There are some units that are really good at close combat, i.e., they are people who specialize in assault actions or urban warfare. But it can’t be asserted that they had 100% units that were 100% capable of fighting in proper close combat at 100% efficiency. And this is unreal and will never happen since there are too many nuances concerning the units’ morale and the real level of training of a particular unit.

One could say objectively that the units formed from the mobilized will conduct a close combat fight dozens of times worse than any contractual unit of either side. Therefore, the picture is as follows: the mobilized units of the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People Republics are not capable of a close combat engagement at distances of 10 to 500 meters because of their low morale. As soon as they are subjected to intense small-arms fire, they attempt to retreat or simply cease their resistance. But as for the enemy’s professional units, they return fire, maneuver, and move around the battlefield. But at the same time, there are professional units, which have the same low morale as the conscripted ones; they try to avoid the battle, retreat, and after that, the artillery starts speaking.

The enemy is different from time to time; they can be very well trained in urban warfare, such as the Wagner PMC. Such an enemy goes into some settlements in company formations specifically to conduct close-up firefights. I would say they wedge into the urban defense of the enemy and conduct an assault action with a number of engineering and sapper operations and so on. That is, the enemy employs tactics similar in some ways to those used in World War I: they use so-called assault units, specifically designed to strike or suppress our defenses with firepower. Subsequently, regular units are brought in to bolster the assault units, consolidate their gains, and fulfill long-term objectives. This enables the enemy to advance, supported by artillery fire and a tactical airforce.

There is another option: I have already told you what happens with the conscripts: they are thrown in waves, and proper, full-fledged infantry close combat does not take place. If there are some specialized units aimed at assault operations, then yes, for sure, they will fight quite well; they know what they are doing, they know their tasks, and, accordingly, they are the most difficult opponents.

As for us, it depends. The situation differs from unit to unit and from commander to commander. For example, UIN 3018 (4th Rapid Reaction Brigade of the National Guard): it performs combat tasks of different specifics, and personnel do close combat in various conditions and, in most cases, come out a winner. I know this clearly because I have fellows who are serving in 3018 as company commanders, deputy company commanders, and platoon commanders; they show me all this, tell me about it, and I kind of understand what the situation is really like.

There are Territorial Defense Forces Units that consist mostly of mobilized troops, and there the situation is similar to that of the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People Republics units. It also largely depends on the commander: how he disposes of firepower, how he arranges the system of fire, how he plans the operation, etc. There are a lot of nuances. As regards the Special Forces units, almost all of our units are capable of prolonged firefights with different units of varying intensities. In this respect, our Special Forces are trained very seriously, and they really do make a difference. So I think that the generalization that everyone in our ranks gets scattered by close combat is utter bullshit and nonsense that does not fit with reality at all.

What do you think about the use of ATGMs in February and March – both domestic- and foreign-made?

I think the quantity and intensity of anti-tank guided missiles use now and in the following periods of time are staggering. In every infantry unit, it was mandatory to have at least a couple of anti-tank missile systems in some variation. We received the Javelin and NLAW anti-tank missiles on the evening of February 26. They were simply unloaded from the transport vehicle, and we were told to use them to their full potential. So we went and used them. The vast majority of the enemy’s armored vehicle losses were the result of artillery and Anti-tank guided missiles fire.

Is it true that the Russians were using old Soviet maps and had serious problems because of this?

We also used maps from the general staff dating back to 1990 or even older. That was not the point.

Did you ever listen to radio intercepts? Was there anything interesting?

No, I did not listen to radio intercepts; we did not listen to them because we did not have appropriate equipment and the Signals Intelligence Units were then far away from our positions. There were a couple of Armored reconnaissance vehicles, which, in theory, could intercept VHF and SW radio communications. But they were not used because the Russian signals intelligence units would probably have immediately identified where these Armored reconnaissance vehicles were standing, and they would have been totally f*cked up. So, no, we did not.

To clarify: if you remember, there was an episode near Kyiv, where I think they published a radio intercept between our soldier and a tanker, when the Russians were trying to hold a circle defense and our fighters said to them “surrender at once”. How do you think this could happen that they reached out to our frequency?

It is quite possible that there can be a situation where both our and enemy units are using radios of the same manufacturer with the same frequency modulation. For example, Baofeng — these crappy Chinese radios — were often encountered. The enemy had no Motorola at all, and as for Harris, well, there is nothing to comment on. Aselsans, which were installed on our tanks, did not appear on the enemy’s side either, so the only options were either Baofengs or cheap Chinese civilian radios, which were used by both sides.

How would you assess the level of assistance the local population provided to the military?

The level of interaction between the local population and the military was quite high. Whenever there was a need for equipment or someone required a ride, the locals readily provided assistance without asking many questions. I appreciate it very much; it helped a lot, and those people who remained in the occupied territories were providing information on the location of the enemy’s headquarters, high-tech equipment (electronic warfare, signals intelligence), and counter-battery radars, which were of interest to certain structures. Back then, if you remember, both the Security Service of Ukraine and the DIU (Defence Intelligence of the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine – ed.) often published photos and technical descriptions of the vehicles they were interested in. It happened quite often, and then these objects were pointed specifically at where they were located, where they were deployed and in 99.9% of cases, this turned out to be true. The percentage of so-called false information was minimal.

Can you say something about the trophy weapons? What did you like best, and what did you not like?

We had AGS-40 Balkan (40mm automatic grenade launcher – ed.); we captured it not far from Irpin, from one of the VDV companies of either the 45th Brigade or the 76th Division; I don’t remember exactly. We used it until it got blown up, along with the operator. Then we had the BMD-2, which we also swiped not far from Irpin. Obviously, there were RPO-A Shmel (rocket-assisted flamethrowers with thermobaric warheads – ed.) and RPG-32s.

Of all small arms, the AK-12 was the most interesting (then the people who took it as a trophy said it was only good for disassembly to get spare parts). We also liked Shmels a lot. It is a very good piece of equipment that can be used to accomplish a variety of tasks. And regarding the AGS we took, it had a handier tripod, was lighter, was rarely seen, but was a very useful thing. As for vehicles, we had only BMDs taken as trophies because we had not reached tanks. And if any of our soldiers had captured tanks, we either handed them over to regular units or left them in the field because we did not have the resources for ammunition or their maintenance, unlike mechanized brigades like the 72nd.

How do you estimate the enemy’s manpower losses?

The enemy losses in my sector (Moshchun, Horenka, Romanivka, and part of Irpin — this is about the later stage of the conflict, not about the Hostomel operation) were quite high. According to my personal estimates, the enemy lost up to 30% of the standard company personnel for various reasons (combat and non-combat losses). In mid-March, there were a significant number of non-combat casualties due to frostbite. The enemy was not prepared for long operations. We inflicted many losses on the enemy during the battles for Moschchun (as mentioned in one of the interviews of the Special Operations Forces fighters). There were quite heated battles, including the operation to install a pontoon bridge to cross to the left bank of Irpin. And on the whole, according to my personal estimation, up to a whole battalion of Russian personnel were killed during these battles.

Is there any information as to how many casualties the Airborne Troops in general and the 331st Regiment in particular really suffered?

I can’t say anything about the 331st Regiment for sure because I am not sure if they were its representatives. But concerning the first stage of the conflict, when there were fights on the outskirts of Irpin and the enemy came close to all the crossings over the Irpin River, the VDV was used as ordinary motorized infantry: they dug trenches and defended certain positions. So I think because of such inappropriate use of paratroopers, they had quite big losses in the units. Starting from Hostomel Airport, where they lost about a company or even two of personnel because, when we retreated from Hostomel, the airport was shelled quite heavily by our artillery. So overall, enemy losses among paratroopers were quite high. I think that they can hardly be compensated by partial mobilization or something else; the losses are too heavy.

In your opinion, was it reasonable to construct defenses along the Teteriv and Zdvyzh Rivers? If so, why weren’t they built?

The point is that the initial plan of the operation implied the deployment of the first echelon of Kyiv’s defense along those rivers (i.e., along Ivankiv). But after making some adjustments, it caused the defense to shift to the line along the Irpin River. Why has it happened? The enemy launched an offensive earlier than planned. Accordingly, the forces and equipment that were defending Kyiv could not deploy along these rivers with the level of losses acceptable for further action. The General Staff at that time, as well as the commanders on the ground, understood that the transportation route from Ivankiv to Belarus was much shorter compared to, for example, the route from Irpin or Dymer to Belarus. Accordingly, the deployment of defense along the Irpin line was, shall we say, a deliberate move because everyone was well aware of the level of the enemy’s logistical capabilities and tried to play around it.

And that strategy worked, as by the end of March, the enemy withdrew from the Kyiv region. It was not due to a ‘gesture of goodwill’ or the completion of their operational and tactical objectives, but rather because their logistics had been depleted. Additionally, I believe the Belarusian side was hesitant to allow the Russians to access ammunition from their depots. And delivery from Russia to Belarus took some time, and logistics simply could not fulfill supply tasks. On top of that, Special Operations Forces and other special designation units were performing certain tasks behind enemy lines, thereby disrupting logistics, which made it impossible to complete the objectives. That is why they failed.

Can you assess the actions of the Special Operations Forces of both Ukraine and Russia and the separate Russian special forces brigades in the battle for Kyiv?

Yes. I do know about the 140th Special Operations Center and the enemy GRU units that operated there. I also know about the individual reconnaissance platoons/companies of the VDV, Kadyrov’s forces, and the Russian National Guard Spetznaz units that were operating in the Kyiv region at that time. The actions of the enemy can generally be assessed as confident and professional, but lacking the assertiveness that our units had.

That is to say, they tried to engage in close combat at a bare minimum: if they had an opportunity to request artillery or some mortar battery to fire on our positions, they would rather request artillery fire than go there in person. There were cases when their special forces units (I can’t say who exactly, as we could not identify them) crossed the river and carried out reconnaissance and sabotage activities on our side. They worked quite well as forward observers: mortar rounds and artillery shells hit precisely where they were supposed to after providing adjustments: they were aiming at platoon strongpoints and our units that were defending their positions. However, our own Special Operations Forces quickly expelled them, and we also battled with the enemy’s forward observers.

So, to say they acted with maximum professionalism and were way ahead of our units would be wrong, because our Special Operations Forces` Units (and in general all forces) showed a high level of professionalism, even in equipment. There were cases when the VDV reconnaissance units (they are considered Special Forces) did not have enough special equipment like night vision devices and thermal imagers, while our special forces units were in a much better position in this respect. And the enemy’s lack of night vision equipment might make them unable to use all their skills and abilities. Our Special Operations Forces units performed better than the enemy’s Special Operations Forces.

What were the tactics of using tanks in the conditions of the Kyiv Region geography?

Tanks were primarily used as ‘assault guns’ rather than engaging in traditional tank duels in the Kyiv region. Although I personally witnessed only one instance of tank vs. tank combat in Horenka, where a tank platoon from the 72nd Brigade entered the village and engaged two shoot-and-scoot T-72B3 tanks from the enemy’s side.

The duel ended with our tankers hitting this tank with synchronous fire from two firing positions on the opposite bank of the river. It turns out that the tank was firing from the side of the glass factory, where they had a firing position. It was hit, there was no epic explosion with the turret blown off, but by the looks of it, the crew was either badly shell-shocked or some of the fire control system elements were damaged. Finally, the tank was abandoned, and it stood there until it was towed away the next morning.

In general, tanks were utilized as assault guns and for infantry support, rather than as breakthrough vehicles. Most encounters involved BMPs or BMDs, both from our side and the enemy’s side. In the direction of Horenka-Romanivka-Moshchun, our units mainly used wheeled Armored Personnel Carriers like those BTR-3Es (I have not seen BTR-4s, but as far as I know, they were there too). Vehicles were used in a very limited and careful manner.

How did Ukrainian aviation perform? Do you know of any cases of enemy planes being shot down in aerial combat?

I cannot say anything about air combat because I have not personally observed it. But at first, our aviation was very active, and as far as I know, even several helicopters over Kyiv reservoir were hit by our fighter aircraft. As to the direct support of the ground troops, there were a couple of episodes when our Su-25s performed skip bombing not far from Irpin, but I do not know more details. In any case, our aviation proved to be most effective, at least because it survived and was still alive at the time of the Kyiv campaign, despite the claims of the enemy’s Ministry of Defense that we had no aviation and no air defense.

What types of infantry armament have had the most significant impact on the course of hostilities? Isn’t the influence of western weapons on the outcome of the Kyiv campaign exaggerated?

Regarding western-made weapons: I first encountered NLAW (although I had seen it before, as I received training on various western weapons, including TOW anti-tank systems) around March 10th. Prior to that, we primarily relied on our own anti-tank weapon systems such as the Stugna-P, Barrier, Korsar, and the American version of the RPG-7 (PSRL-1). And our National Guard anti-aircraft forces made do with either Igla or Strela MANPADS. So we first saw things like the Stinger sometime in March, around 28th-29th. Therefore, I think that the Western models of antitank and man-portable air-defense system weaponry have played a significant role, but the most important was the knowledge, motivation, and desire of ordinary, junior, and senior commanding staff to win.

And what about the hyped up NLAWs that were also used in the Kyiv area?

Well, this thing is like a crazy woman because you shoot at an enemy BMD and it targets a f*cking car instead. That’s why it’s so f*cked up. I won’t say that NLAWs are a bad thing; they are quite effective, but the firings that my unit did were not very successful. And that wasn’t because of the low level of professionalism of the anti-tank guided missiles operators.

I have heard it said that the Pions (203mm self-propelled howitzers) saved Kyiv at the start of the war. What do you think of the Ukrainian high-power artillery?

Generally, Ukrainian artillery, in particular the 72nd Brigade and its brigade artillery group, and the artillery of the 80th Air Assault Brigade, showed incredibly strong results. I knew where Pions were located (in Divychki), all these shells flew over my position, and I could perfectly hear them flying.

At night, the situation was the following: I could hear a convoy coming (at a great distance, but I could hear it because it was big and there were a lot of vehicles), and somewhere in the distance I could hear artillery fire. It was clear that it was not 152mm but something more powerful. A quiet, hardly audible burst of shells, loads of explosions, and silence. And that’s it — no convoy anymore. After 5–10 minutes [of shelling], there were huge f*cking flames.

So I can say that artillery was doing everything possible and impossible to defend Kyiv. And for the most part, the crushed convoys with tank wrecks that you have seen at that time were all due to artillery work.

What about the performance of regular Ukrainian and Russian artillery units? How would you assess their effectiveness?

I have been in the middle of artillery duels: our crews of self-propelled artillery divisions, towed howitzers (if we are talking about 2A36 Gyacint-B), mortar batteries have shown incredible efficiency and effectiveness.

I can explain using the example of a mortar battery of one of the military units of the National Guard: the guys very quickly learned how to fight. Before [this understanding], they had mainly firing trainings, and, let’s say, they had minimal time to deploy: they arrived, fired, and left. All of this, combined with a heavy barrage against enemy positions, took approximately 15 minutes, while the return fire arrived after about 20-25 minutes, but with significant dispersion. Even if the mortar men were precisely targeted, it would be unlikely for them to be hit. The mortar batteries from the other side were most likely Vasilki (82mm gun-mortar) or regimental level 120mm mortars; there was a wide scattering there.

Regarding the performance of large artillery (122mm, 152mm), they fired intensively, but they were unable to engage in a counter-battery fight with our units. Our units were faster and more accurate, causing the Russians to quickly abandon their positions. Therefore, there is no need to discuss a counter-battery scenario. Although it was present at first. Roughly speaking, in the two weeks since we were stationed in Horenka, they regularly played this biathlon there, and fortunately, our units in most cases won the artillery duel. So I think the effectiveness was extremely high.

To what extent did the destruction of the dam at Demydiv contribute to the defense of Kyiv?

Quite a significant role, because the enemy found the exact spot on Moshchun that I mentioned above. It was a narrow section of the river, so it was a matter of 15 minutes to deploy the pontoon, which they did: the Russians dropped the pontoon under the cover of smoke [made by smoke machines]. Thermal imaging cameras did not see anything, all the optical reconnaissance means and drones were useless. So the location of the pontoon had to be found by a recon unit on foot. It was discovered just near Moshchun. On March 4-6 there was harsh fighting to take control over Moshchun. And if the dam had not been blown up, the enemy could have deployed the pontoons indefinitely. Well, blowing up the dam widened the river, created a swamp [on both sides of the river], 200-300 meters to the left and right. Just in order to reach the river, they had to use the vehicle-launched bridges to pave the way. So it played a very significant role and made it impossible for those enemy units to advance and cross Irpin.

Can you say something about electronic warfare (EW), both ours and the enemy’s?

I have never experienced any problems with radio communication or phones, so I don’t know how our and the enemy’s EW equipment worked. Maybe our radios were just very cool and were just outside the range of the enemy’s EW stations. Or those EW stations were aimed at performing completely different tasks for the enemy. I think that they were tasked with covering the headquarters of the enemy groups or some important supply hubs. But I did not experience the effect of EW no, there was no such thing.

How did the Bayraktar TB2 unmanned aerial vehicles perform in the Kyiv direction?

In general, during the first phase of the conflict, before the enemy even realized that UAVs were actually operating here, the Bayraktars were quite effective: both as a standalone combat element (a drone with bombs and missiles) and as an element of a reconnaissance-strike complex. In the first case, they actually operated until the end of February and, as an element of the reconnaissance-strike complex, during the entire Kyiv campaign. They had a sufficiently powerful optical-electronic channel, which allowed them to easily reach Irpin and Bucha from the outskirts of Kyiv and conduct artillery fire adjustment and fire control.

In other words, neither the EW systems nor the air defense systems of the Russian VDV troops in that region were able to counteract effectively?

No, they could not deal with the UAVs.

Which Ukrainian and Russian armored vehicles have you encountered? What can you say about them?

Traditionally, all of our units have Armored Personnel Carriers: mainly Varta, from the manufacturer Ukrainian Armor. The main vehicles are the standard Varta, the Varta-Novator, the first versions of Kozaks that are without prefixes. We’ve had them in various modifications with ’sockets’ acceptable for installation of the AGS-17, the Barrier anti-tank guided missile, and the NSV Utyos (a Soviet 12.7mm caliber heavy machine gun). The Kozaks were equipped with PKM with a machine gunner on top. From all these vehicles, I liked the Vartas more because they were fairly easy to maintain, unlike the Kozaks which were dependent on IVECO’s spare parts.

The Varta (based on MAZ 53, as I remember) is well armored. There were cases when they were blown up on the TM-62 (a Soviet anti-tank mine) and not even the front axles were ripped out, but of course the engine was ruined and there was nothing to be done in terms of repair there. I was driving all three vehicles, and the most comfortable to drive was the Varta-Novator. Its automatic gearbox is a debatable decision, but you can switch to manual there. It has a low silhouette (unlike the usual Varta), high dynamic performance, good cross-country ability; and, most importantly, a good compartment for additional equipment. We used vehicles for ammunition supply, transporting wounded, and as a means of transportation to rally points. I can’t say anything bad about the Kozak, either: it really saved lives in many cases of active combat operations in the Kyiv campaign.

Concerning the captured armored vehicles: the only one I ever saw was the KAMAZ Typhoon-K. I do not know its further fate, but in general, being used as an Armored Personnel Carrier, it was able to perform well enough in those circumstances. We captured it from the Russian National Guard. But in general, Russian armored combat vehicles’ characteristics were not bad, but only due to the foreign components they were made from, as proven by practice. For example, IVECO Rys vehicles that were used by VDV units and involved in the operation near Kyiv. Well, many have seen trophy Tigers, but they could hardly be called Armored Personnel Carriers or Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles, because their protection was only good against small arms firepower. But I have not driven any of the listed Russian vehicles; my experience is limited with our MRAPs.

What can you say about your counterparts from the National Guard of Russia (Rosgvardia)?

I want to say that these guys were not prepared for war in any way. After the blown up of the Hostomel bridge, were found tilt-covered KAMAZ trucks loaded with riot armor, aluminum shields for protection, rubber truncheons and all kinds of special equipment like Cheryomuha (a chloroacetophenone gas grenade), etc. This proves they were preparing to suppress the social unrest that would result from the overthrow of the legitimate government, and they were forced to resort to military action instead; they were not expecting that.

I mean, as proven by practice, their level of combat training was minimal compared to even the Ukrainian National Guard’s public security protection units. The practice has shown that personnel of the similar Ukrainian unit 3030 were able to perform military missions, in contrast with the Rosgvardiya. Only some of their units could be paid attention to, such as special designation units within the Russian National Guard, for example, kadyrovtsi. Today they are laughed off, but at first they even tried to storm fortified positions on our shore. But mostly there were ‘astronauts’ (slang meaning riot policemen that are usually wearing specific helmets).

Given your considerable years of service in the Army and your level of familiarity with the Defense Forces ‘behind the scenes’ work, you must have had your own expectations and probable scenarios once the war started. What did you initially expect from a full-scale invasion?

Based on my skills, experience, and understanding of modern warfare, I expected precision strikes on civilian infrastructure: the power plants, the electricity-distribution systems, and the Vyshhorod dam. If they had hit the dam, it would have triggered a disaster and made it difficult to move Kyiv defense forces and equipment to the deployment lines, where the organized defense should have been. And therefore, the enemy would have been able to rush painlessly and unhindered through Vyshhorod and appear at the Kyiv gates.

I also expected that the enemy would try more actively to suppress our air defenses, that it would use high-tech weapons against air defenses (like anti-radiation missiles), and strike more precisely with missile weapons. And in general, I expected more aggressive tactics from the enemy. Instead, they were not overly aggressive when it came to the final stages of the Kyiv campaign (i.e., after they failed in Hostomel Airport, and during the Moshchun and Horenka defending.) The intensity of close combat fighting gradually dropped and became more of an artillery duel, and finally they simply could not cope with logistics. My expectations were a little harsher than what happened in reality, and that’s for the best.

Why did the Russians retreat from the north? What do you think?

First of all, as I have already said, due to the logistics issues. The second moment: we had very good operational planning and management of all our troops and units by Colonel-General Oleksandr Syrsky, the Commander of the Ground Forces of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. And, therefore, the personnel’s high level of skills and training of troops. I mean, fighters, contract staff and officers, companies, battalion commanders, some special purpose units — they all showed class, and I think they played a big role in the Kyiv defense campaign’s success. The Russians retreated simply because, to quote the classic, they got screwed.

What is the most memorable moment of the battles in the Kyiv region for you?

The most memorable episode of the Kyiv campaign was the night battle in Moshchun, when the enemy somehow (I still don’t understand how) crossed the river with armored vehicles and BMDs. This happened somewhere around March 10th-11th. I don’t know how many night vision devices the enemy possessed, but as I understood, not a lot, because we didn’t find any night vision devices on any of the Russian soldiers. They rolled over with vehicles, with standard armament. Apparently, that was one of their companies that crossed the river. But it was incomplete: there were 80–86 people, including the officers. They entered the settlement and began to move swiftly to the south of it, i.e., to the road, which should theoretically lead them to Horenka, and then — to Pushcha-Vodytsia.

We’ve been told about the breakthrough at about 1:30 a.m., so we immediately set out to the area, walked about a kilometer, and then discovered how they were deploying in battle formations. The Ukrainian National Guard units that were in our neighboring unit in Vyshhorod were already fighting them. Some other units were also involved, as far as I understood — it was Azov, and either Territorial Defense or Special Operations Forces, I don’t know exactly, but some of them. And one of the companies of the 72nd Brigade, maybe the 5th one. We had no armored vehicles there, so the advantage was on the side of the enemy. But they didn’t have Night vision devices in most cases, so it was some kind of strange disco: tracers were flying somewhere in the air, and targeted shooting was out of the question.

So, since we knew there were no civilians in the settlement, we requested an artillery strike. With the beginning of the artillery barrage, we started using the Anti-tank guided missiles we had (by the way, these were NLAWs), and then our marksmen started to precisely knock out the enemy with UAR-10s (a 7.62×51mm NATO sniper rifles manufactured by Ukranian company Zbroyar and based on the ArmaLite AR-10) from the hill. I suppose that after 20–30 casualties, they delved into total chaos: as soon as they saw that their BMDs were already burned, they just started running towards the river. Well, while they were running, they all got slaughtered there. The fight was very dynamic, and colorful (such an impression was due to the NV device). But finally, for sure, in the morning there were a pile of corpses in Moshchun, the burnt out BMD – the results of this fight that I saw on video.

So it seems that was the only chance for them to use amphibious vehicles to take advantage?

Yes. I think they probably somehow found a place for the three BMDs to cross the river.

Do you think Russian troops will attack Kyiv again? What would be the outcome of that?