The “People’s Republics” Technology

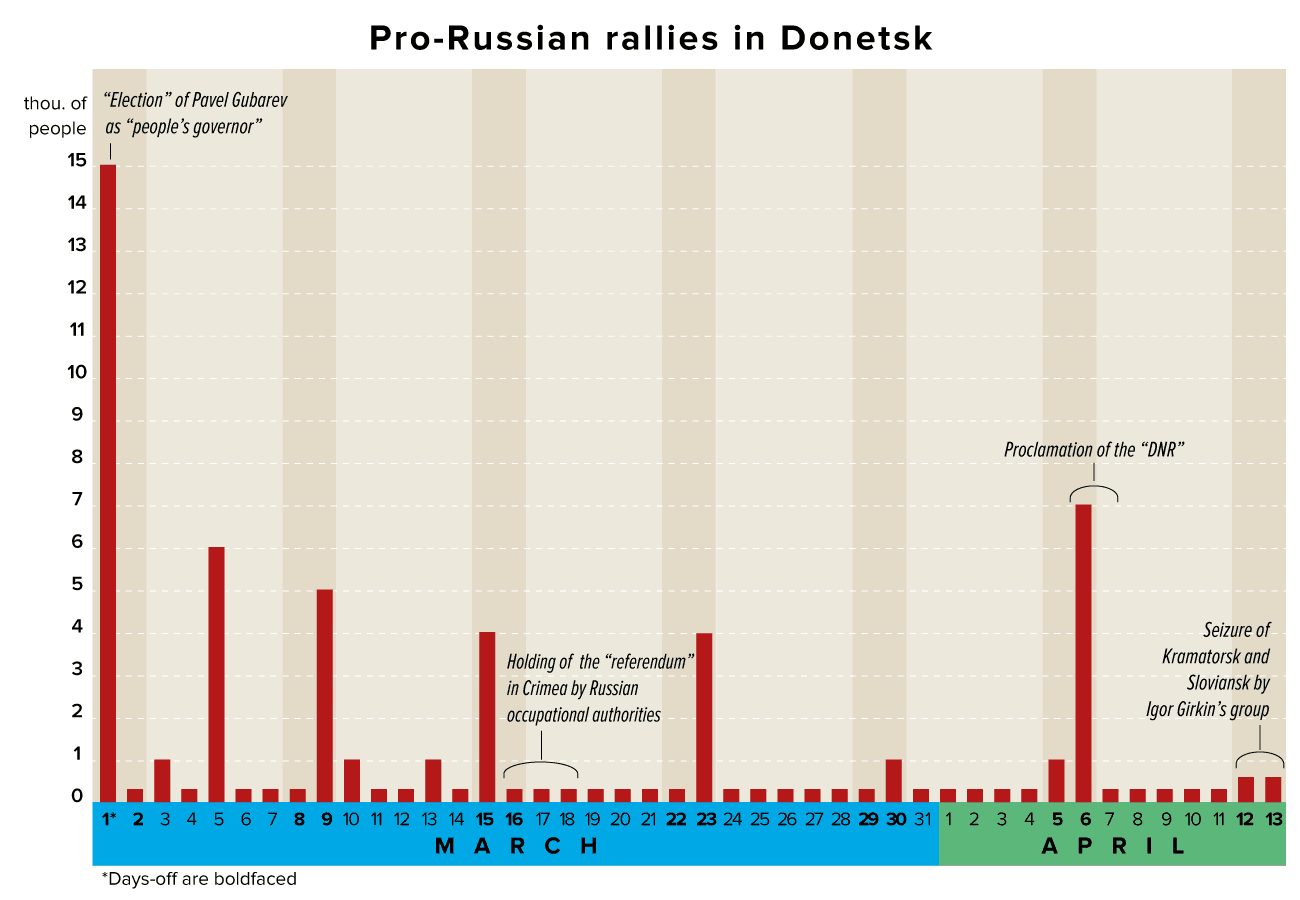

From early March to early April, the activity of pro-Russian protests began to wane. Take Donetsk as an example of the protest dynamics: the big rally on March 1st gathered up to 15,000 people, at the March 5th rally, the number of protesters was estimated at 7,000, the March 9th rally, up to 5,000. After the March 13th clashes, which left one Ukrainian activist dead, the next rally (March 15th) gathered around 4,000 people. And although rallies did not stop completely, they usually gathered no more than 1,000 demonstrators. Many factors contributed to the decrease in activity: time, fatigue, and even the actions of the official Kremlin, which on March 18th unilaterally joined annexed Crimea to Russia, which was rejected by some of the moderate Russian sympathisers. Ukrainian intelligence agencies also had their role: in the first half of March, they identified and detained several “people’s leaders” who had been carrying out the plan of action dictated by Sergei Glazyev from the Russian Presidential Administration.

That the protests were petering out, and the southern and eastern regions of Ukraine were returning to normal life, was understood in Russia. Preparations were made for the change in the format of protests, including the establishment of “people’s republics,” their proclamation, and local referendums that had to legitimise them, were to have taken place on the eve of the May 25th presidential election. However, this process, too, began earlier than was planned.

In March, SBU officers Oleksandr Petrulevych and Oleh Zhyvotov in March were assigned to work in Luhansk by Valentyn Nalyvaichenko. It was they who promptly detained Kharitonov, the “people’s governor of the Luhansk region,” in the very first days of work. In the following weeks, they exposed a network of militants and agents of the security services of the Russian Federation—the so-called Army of the South-East. At the time, the network was just being formed and accumulating weapons. Its main task, determined by the Russian leadership, was the disruption of the May 25th presidential election and the holding of a “referendum on self-determination” at the drop of a hat. The referendums were expected to be held simultaneously across all south-eastern regions of Ukraine, and the network was engaged in preparing just that.

The detention of key individuals of the group began on April 5th, at 5:00am. 40 searches were carried out in Luhansk and seven other cities; 12 leaders of the network were arrested. Among them was Alexey Relke, a Russian intelligence officer, the leader of the entire network. 300 weapons were removed and taken to the SBU office in Luhansk. Three leaders—Bolotov, Ruban, and Mozgovoy—managed to escape.

Relke’s detention prompted pro-Russian forces to take a desperate step—an assault on the SBU office in Luhansk, where Relke was being held and where weapons were stocked. That is why, on April 5th, Valery Bolotov recorded and posted on social media a desperate video appeal, explaining the need to act by a wave of arrests of their followers. He took off his Balaklava and, on behalf of the “Defence Staff of the Southern East,” encourages all residents of those regions to take to open resistance in order to translate their plan into reality.

On April 6th, an assault on the SBU office in Luhansk began. First, a crowd gathered near the building, and its representatives, including Afghan veterans and local “Cossacks,” entered the SBU office. They demanded the release of the detainees. Finally, an assault on the building began. The police, who were near, showed indifference and did not prevent the assault.

There is a trick in this story: SBU officers and the police leadership blame each other for ceding the SBU office building. It is because the released leaders of the militants, including Alexey Relke, recorded and released a video message where they thanked the head of the Luhansk SBU, Oleksandr Petrulevych, for the release and weapons. The relevant authorities are yet to have their final say in this regard.

It can be safely assumed that the assault on the SBU office in Luhansk was a catalyst for all events in the Donetsk region, since it set in motion irreversible processes. Prior to this, there had been assaults on civilian institutions only, such as regional state administrations. The SBU was a high security facility and had a large weapons arsenal. Those weapons were immediately given to the pro-Russian forces in Luhansk, who set up barricades before the SBU and assigned their guard. The assault of the SBU office can be considered a desperate act, since those criminal acts were to be severely punished by the Ukrainian authorities, so pro-Russian forces in Ukraine had to act without delay if they relied on success. And they began to act.

On April 6th, not only did the assault on the Luhansk office of the SBU take place: This day became the key one, with the Russian plot beginning to be implemented. Attempts to gather people for large-scale rallies and seize local power took place in seven regional centres in total, but they failed in Odesa, Zaporizhzhia, Mykolaiv and Dnipropetrovsk. On the afternoon of April 6th, pro-Russian forces seized the Donetsk regional state administration again. They gave the deputies of the regional council until midnight to hold an extraordinary session and decide on a referendum on the accession to Russia. On the evening of April 6th, the Kharkiv regional state administration was seized. On the night of April 6th to 7th, at 3:40am, members of the “People’s Militia of Donbas” broke into the building of the Donetsk office of the SBU, occupied the ground floor, and allegedly prepared firing points.

On the afternoon of April 7th, the so-called “Donetsk People’s Republic” (DNR) and “Kharkiv People’s Republic” (KhNR) were proclaimed. The “People’s Council” in the Donetsk regional state administration decided to join “the newly formed republic” to Russia. The “People’s Council” had been created by groups of pro-Russian forces, since the current local deputies of the Donetsk region did not turn up at the session where the accession to the Russian Federation were to be discussed. Those events were described by the journalist Denis Kazantsev:

“On the same day, the crowd, which had spent the night in the Donetsk regional state administration building, proclaimed the ‘Donetsk Republic.’ It was at the seized session hall, which people entered right from the street. Those who made it first to the seats of regional deputies voted for the ‘sovereignty’ in the end. […] That is how ‘DPR Parliament’ appeared.”

Alexander Borodai, a Russian political scientist and PR counsellor, the Malofeev’s employee, will soon become the first ‘Prime Minister’ of the proclaimed DNR.

On the evening of April 7th, the Acting President of Ukraine, Oleksandr Turchynov, announced the creation of the Anti-Crisis Headquarters:

“Yesterday, the second wave of the special operation of the Russian Federation against Ukraine started, seeking to destabilise the country, overthrow the Ukrainian authorities, disrupt the elections, and tear our country into pieces. […] Ukraine’s enemies are trying to play out the Crimean scenario, but we will not allow it. […] The Anti-Crisis Headquarters was created; those who have taken up arms will face anti-terrorist measures.”

And those measures began. On the same evening, the SBU office in Donetsk was seized back without victims. The next day, April 8th, at about 6:30am, the “Kharkiv People’s Republic” (KhNR) ceased to exist. Officers of the Vinnytsia-based Jaguar special operation unit entered the Kharkiv regional state administration and detained all those present without any shot, noise grenades or other special weapons. The key individuals involved in the creation of the “KhNR”—Konstantin Dolgov and Yegor Logvinov—were arrested immediately or in the days that followed.

A Third Try

Despite changes in the initial plan, the “Russian Spring,” did not bring real results. There were no mass demonstrations in eight south-eastern regions, calls for referendums and accession to the Russian Federation, even voiced out not by local deputies but at least by crowds in administrative buildings. The pro-Russian movement lost many of its leaders captured by Ukrainian authorities, it was not as powerful as in early March, and controlled the administrative buildings in Donetsk and Luhansk only.

For the Russian leadership, the situation had to be rescued, and in an urgent manner. Without further intervention by Russia, Ukraine would soon have returned full control over its regions, and Russia would have ended up in a situation where there was consolidated “continental Ukraine” and annexed Crimea. The attention of both Ukraine and the world community would have been focused on it. There were no human resources and leaders in Ukraine capable of radically turning the situation around for Russia’s benefit.

On 9 April 2014, another story with Alexander Borodai was shown on Den’-TV:

“In fact, if green men were now to appear in eastern Ukraine en masse—or the mere fact of their presence were to be confirmed—this would certainly provoke a different reaction of the entire western world with regard to Russia. And it would have to bear a really heavy burden on sanctions, which could be introduced by the United States and Western Europe.

“[And if they were to be volunteers,] the volunteers movement has a great history in Russia, and it does exist. The problem, however, is that a sort of coordination centre is necessary to accept volunteers.”

And on the morning of 12 April 2014, a Russian subversion group under the command of retired FSB colonel Igor Girkin, a former FSB officer, the head of the security service at Malofeev’s Marshall Capital and reenactor in civil life, seized the Ukrainian cities of Sloviansk and Kramatorsk. Another group under the command of lieutenant colonel Igor Bezler captured Horlivka. On April 13th, flags of all eight “people’s republics” in eastern and southern Ukraine were posted online. Flags had been created as variations on the Russian tricolour, following the example of the “DNR” flag that already existed at the time. The appearance of eight flags would not have been so strange but for the fact that the “Luhansk People’s Republic” would only be proclaimed on April 27th, and that it used one of the flags published online as far back as April 13th.

On 17 April 2014, at an annual press conference, Putin stated:

“Let me remind you, using the terminology of the tsarist times—it is Novorossiya. And Kharkiv, Luhansk, Donetsk, Kherson, Mykolaiv, Odesa were not part of Ukraine in the tsarist times. All those territories were given to Ukraine in the 1920s by the Soviet government.”

Such a statement could not have been accidental. At the highest level, there was a call designed to mobilise both Russian supporters in Ukraine and Russian radicals ready to go to Ukraine to create “Novorossiya.” In his statement, Putin made a factual mistake: historically, Kharkiv never belonged to the Novorossiya province, being part of Slobozhanshchyna (Sloboda Ukraine). But this mistake could hardly have been accidental: taken together, all that clearly corresponded with Russia’s intentions to support an unrest and prepare a background to secede those regions from Ukraine.

This is not the first Putin’s statement in the spring of 2014 which was both deceptive and provocative. Even on March 18th, during the ceremony of the “accession” of Crimea to the Russian Federation, Putin said that the Bolsheviks had joined the South of Russia to Ukraine without allegedly taking into account its ethnic composition. It, too, was nothing more than an attempt to rewrite history and a blatant lie: With the exception of Kuban, the current borders of Ukraine almost exactly cover the areas of the settlement of ethnic Ukrainians. Ukrainian population constituted the majority in eight southern and eastern regions both in the late 19th century, during the Russian Empire, and in our time, as proven by all censuses starting from the first one held in the Russian Empire in 1897.

Therefore, there was another change in the idea of the “Russian Spring”: instead of demands for federalisation from regional councils, armed groups appeared, “people’s republics” were proclaimed, and this impetus—fighting for the secession of eastern and southern Ukraine—was simultaneously supported by Russian news media with Putin in the lead. Armed confrontation was initiated not through local mediators but directly through Russians who were called ‘volunteers.’ This took the conflict to a new level, without letting it go out.

The map of the distribution of the dialects of the Russian language. The Ukrainian language is marked as the ‘Little Russian’ dialect. The boundaries of the distribution are determined by the majority of speakers.

The Backside of the “Russian Spring”

It would be naïve to believe that all events of the “Russian Spring” were orchestrated from the Kremlin, and everyone involved in it worked for, or were paid or hired by, the Kremlin. It is not true: There were passionate supporters of Russia in Ukraine, who supported it purely because of their own convictions. The Russian authorities channelled their dissatisfaction to achieve their goals.

Nor are there any grounds for considering Malofeev and his entourage the sole authors of the idea of Russia’s invasion into Ukraine for the division of its sovereign territory. There is evidence that the idea of separating the southeast regions of Ukraine and the creation of “Novorossiya” had long been worked out at the Russian Institute for Strategic Studies (RISS), which used to belong to the Foreign Intelligence Service of the Russian Federation, and since 2009 had been subordinated to Russia’s Presidential Administration.

The Malofeev group, however, did play a significant role in the events and decision-making during the annexation of Crimea, and, more importantly, in initiating the war in eastern Ukraine.

Girkin himself argues that the idea of the “Ukrainian campaign” was his own. In addition, in November 2014, he admitted in an interview that he “pulled the trigger of war.” At first sight, such confessions to his own crimes and taking responsibility for the beginning of the war may look like a kind of noble gesture, but this act should be approached in a different way. He admitted the obvious—who began the fighting—but only in order to create the image of “truthteller.” He used this image for the sole purpose of persuading others that the beginning of the war was also his own idea and responsibility, drawing attention away from the Russian authorities—the real initiator of the events that began to gain inevitable momentum in Donbas after the first shots.

The scenario of the developments in Donbas shows that there is a clear parallel with the events in Crimea. The difference is that, whereas the situation in Crimea, where the Russian Navy was partly based under an agreement with Ukraine, gave the Russian authorities the opportunity to feel more confident and use troops disguised as “self-defence,” in Donbas the Kremlin tried to act through “volunteers” who were allegedly acting at their own initiative. The implementation of this “own initiative” was entrusted to the Malofeev group. In Crimea, in the event of failure, it was always possible to “save the face” to some extent, since the troops did not have any insignia. In the case of Igor Girkin’s “personal group,” making excuses would have been easier, since it was impossible to reasonably prove its connection with the Russian authorities.

In such circumstances, Malofeev’s political scientists and “reenactors” were convenient and “cheap” in terms of responsibility for the Kremlin. And if they could have achieved the desired result—to prevent the conflict in Donbas from dying out and escalate it further—they would also have been extremely effective. A ‘hot’ armed conflict could, in turn, have continued to give rise to the use of regular Russian troops—as fake peacekeepers or in some other way, depending directly on the further development of the conflict. History showed that regular Russian troops had been involved in the conflict since the summer of 2014.

Still, Malofeev’s motivation was unclear: What made him agree to such a role? In fact, his position looks like a non-ironic example of “voluntary-compulsory” motivation. First, Malofeev had previously been implicated in actions that characterise his relationship with the Russian authorities as “symbiosis.” For example, his Safe Internet League became one of the main initiators of Internet censorship laws, making it look like the demand for bans had come from civil society. Second, Malofeev owed the state bank a big sum of money in early 2014 and was being investigated in a criminal case. It was effective leverage that the state used against him. A year later, more than 80% of his debt was written off, and the criminal case closed. The “irresistible offer” was reported to have been given Malofeev at the Presidential Administration, namely that his people would be used to initiate a new phase of the conflict in Donbas in exchange for his debt being written off. Finally, the idea of joining Ukraine, fully or partly, to Russia is not alien to Malofeev himself for ideological reasons: He is a convinced monarchist, a conservative, and a supporter of the ideas of Russian imperialism.

This led to the mutually beneficial nature of their relations: The Russian authorities used Malofeev’s and his people’s services in matters for which they did not want to bear direct responsibility.

The Russian Narrative

The question of who exactly is responsible for taking tension in Ukrainian society to a new level of escalation, which grew into military action—or, putting it simply, “Who started the war?”—is one of the key questions for Russian propaganda.

In this regard, Russians made up several “levels of protection”—the arguments that are typically used in discussions.

The first and most primitive “level of protection” is an appeal to Turchynov’s announcement of the beginning of the Antiterrorist Operation following the events in Sloviansk on 13 April 2014, and, therefore, he is the one who “started the war.” This is a preposterous claim since Turchynov merely reacted to the seizure of the city the day before, on April 12th, by a well-prepared and well-armed group, which seized all key government agencies and raised a foreign flag. Consequently, this argument of Russian propaganda is dismissed even under superficial consideration.

The second “level of protection” is the reference to the fact that the anti-terrorist operation was allegedly proclaimed by Turchynov long before Girkin had turned up in Sloviansk, on April 7th. In fact, it was the establishment of the Anti-Crisis Headquarters, announced by Turchynov on the evening of April 7th, following the simultaneous proclamation of two “people’s republics” in Ukraine on that day. The only known operation of the Anti-Crisis Headquarters was the bloodless re-capture of the Kharkiv regional state administration on the morning of April 8th and some other preventive actions, including the forced march of the 80th airmobile brigade to Luhansk airport. In no way do all those actions live up to “the resolution of an aggressive war,” and so the third “level of protection” gets into the act.

It offers the following account of the events: The war was really started by Igor Girkin, a former security service officer, who had nothing to do with the Russian state and the FSB, and his group were mere volunteers. Everything that happened was his own responsibility, his personal initiative, and, of course, the responsibility of the Ukrainian leadership, which “was unwilling to negotiate.” With this account of the events, Russian propaganda tries to pretend that there is a clear distinction between, in fact, the Russian state and some volunteers acting on their own behalf. This is an attempt to overshadow the fact that Russia had long been in decay in many aspects. Its government apparatus merged with security services, the church, oligarchs, criminals, private mini-armies, private business, and news media, forming a tight knot. The Russian authorities dubs everything it does not want to bear responsibility for as the private initiative, and easily deny anything that prevents it from doing so. Putin’s regime has long been interwoven with all power centres in Russia. Unravelling this knot and proving Russia’s connection with the preparation and conduct of the aggressive war against Ukraine at all levels will be a challenge for future prosecutors and judges.

Afterword

In considering the events of the spring of 2014, the invasion of Igor Girkin’s group needs accurate assessment. That the Kremlin used his services is indicative of not the successful implementation of Russia’s plans for Ukraine but one of the latest attempts to turn the situation around in its favour, when much more successful scenarios had failed. Russian researchers, including Dmitry Labauri, believe that Russia’s ideal plan in the spring of 2014 would have been Ukraine’s full federalisation. Thus, control over the whole of Ukraine would have been preserved, and Russia would have avoided any accusations against itself. Labauri says that this plan was offered by the liberal-moderate forces in the Kremlin, probably led by Surkov.

The “party of war” was in place, too. In March—April 2014, the Russian leadership considered the possibility of its troops deploying in mainland Ukraine. The role of “hawks” here was played by Shoigu and Glazyev. The large-scale invasion plan immediately after or together with the annexation of Crimea never came true—perhaps, the arguments of the moderate forces on the possible negative consequences, including for the economy, were more convincing. But as time wore on, no success in imposing federalisation on Ukraine was in place. Therefore, the bet was made on so-called “volunteers.” The Kremlin believed that the Ukrainian Army and the state would not be able to withstand them.

So, at the beginning of the conflict, the Kremlin had at least two scenarios for Ukraine:

- “All pro-Russian Ukraine,” a Russian imperial project which was lobbied by liberal and moderate forces. The achievement of such a result would be possible due to the coming of pro-Russian forces into power and the overthrow of the new Ukrainian authorities and the Ukrainian patriotic movement in general. More “neutral” variations of the plan, which were less overtly pro-Russian, were possible, too: a federalized Ukraine; a neutral non-aligned Ukraine; and Ukraine as a confederation. In other words, Ukraine had to be completely transformed into an object incapable of conducting its own foreign and domestic policy because of the impossibility of accommodating several regions. In such a case, Ukraine would remain under the economic, political, cultural, and religious influence of Russia.

- “Great Novorossiya,” a Russian nationalist project aimed at dividing Ukraine and creating a buffer and dependent state from Kharkiv to Odesa, which was lobbied by “hawks.” The newly created buffer state, Russian ideologues argued, would be economically capable, have access to the seas, and, most importantly, significantly undermine the Ukrainian state, isolating it from the seas and undermining its economic power.

It was impossible to implement those two projects at the same time. Their implementation required different methods—either through political, diplomatic and economic pressure or by force. In the case of force, all diplomatic and political efforts would have come to a naught: Negotiating the conditions for mutual existence within Ukraine as a unitary state at a time when armed forces were declare the idea of creating a separate state would have been impossible. Force is a direct indication that talks are completely useless.

The inadequacy of the Kremlin regime was in its failure to choose a single tactic and stick to it. Instead, it was attempting to kill two birds with one stone, ending up with nothing but Crimea, which is not recognised by the international community, parts of two Ukrainian regions—and hostile Ukraine.

Due to the lack of political will to follow one option, the Kremlin failed to deliver the “Novorossiya” project, consisting of at least eight regions, through its armed force when it was possible. Nor did it force the official Kyiv to turn Ukraine into a state-like entity, deprived of its own free will.

In a speech at the Donuzlav youth-patriotic camp in Crimea in 2018, Glazyev said of the events of the spring of 2014:

“We had to free the whole South-East [of Ukraine]. Why did we not? I think this is the result of a Western provocation. Western leaders made it clear to our leadership that they would recognise Crimea as part of Russia. But if the “Russian Spring” continued, with other regions acceding to Russia, there will be a third world war. It was hoax. They did not recognise Crimea but used it as a ground for sanctions. The war in Ukraine began because we had not freed the South-East. If we had protected it, there would be no war today, there would not have been dozens of thousands of casualties. The Kyiv regime would have managed to survive only in Kyiv and western Ukraine. It was, I believe, the worst strategic mistake.”

Among the reasons for the total failure, Russian nationalist Alexey Kungurov, Igor Girkin’s associate, named Russia’s failed information policy in Ukraine, for which Alexey Chesnakov, a member of Surkov’s team, was directly responsible in the spring of 2014. Perhaps Chesnakov did not really do what he was supposed to. Perhaps Russians really underestimated the ability of the Ukrainian intelligence to detect and hold back leaders of the Russian party. Still, the main reason for the failure of the “Russian Spring” was expectations of Ukrainian citizens in southern and eastern regions supporting the collapse of their own state in favour of the Kremlin, which were completely inconsistent with the reality.

Read also:

The contents of the article are licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. Copyright exceptions are marked with ©.

The article was prepared with the assistance of the Ministry of Information Policy of Ukraine.

SUPPORT MILITARNYI

Even a single donation or a $1 subscription will help us contnue working and developing. Fund independent military media and have access to credible information.

Vadim Kushnikov

Vadim Kushnikov

Андрій Тарасенко

Андрій Тарасенко

Юрій Юзич

Юрій Юзич

Віктор Шолудько

Віктор Шолудько

Роман Приходько

Роман Приходько

Андрій Харук

Андрій Харук

Yann

Yann

СПЖ "Водограй"

СПЖ "Водограй"

ГО "Військова школа "Боривітер"

ГО "Військова школа "Боривітер"