By early April 2014, the “Russian Spring” had all the signs that it would soon cease as a phenomenon. The regional council deputies in all Ukrainian regions did not support the demands dictated by Kremlin advisers. Those included the non-recognition of the Verkhovna Rada (Ukrainian Parliament) as a legitimate body; the creation of alternative executive bodies, and the re-subordination of local law enforcement agencies to them; suspension of transfers of taxes and duties to the state budget; the change of the state structure of Ukraine to federal or even confederative; and, most importantly, inviting Russian troops to “protect the local population.” Pro-Russian rallies gathered fewer and fewer people.

At the same time, Ukrainian law enforcement agencies and security services neutralised the efforts of Russian agents’ networks, with “people’s governors”—Ukrainian citizens recruited by Russian special services and ordered to proclaim the Kremlin demands—being detained in Odesa, Donetsk, Luhansk, and Kharkiv. On April 7th, the “people’s republics” in Donetsk and Kharkiv were completely virtual: They had neither force nor leaders.

The Kremlin was forced to immediately save the day. Since the locals, citizens of Ukraine, had failed to meet their assigned tasks, the mission was entrusted to Russians. Igor Girkin, Alexander Boroday and other “volunteers” were supposed to take the conflict to a new level and not let it go out. They did not expose their origin, hoping to quickly complete the mission and waiting for the Russian army’s speedy approach.

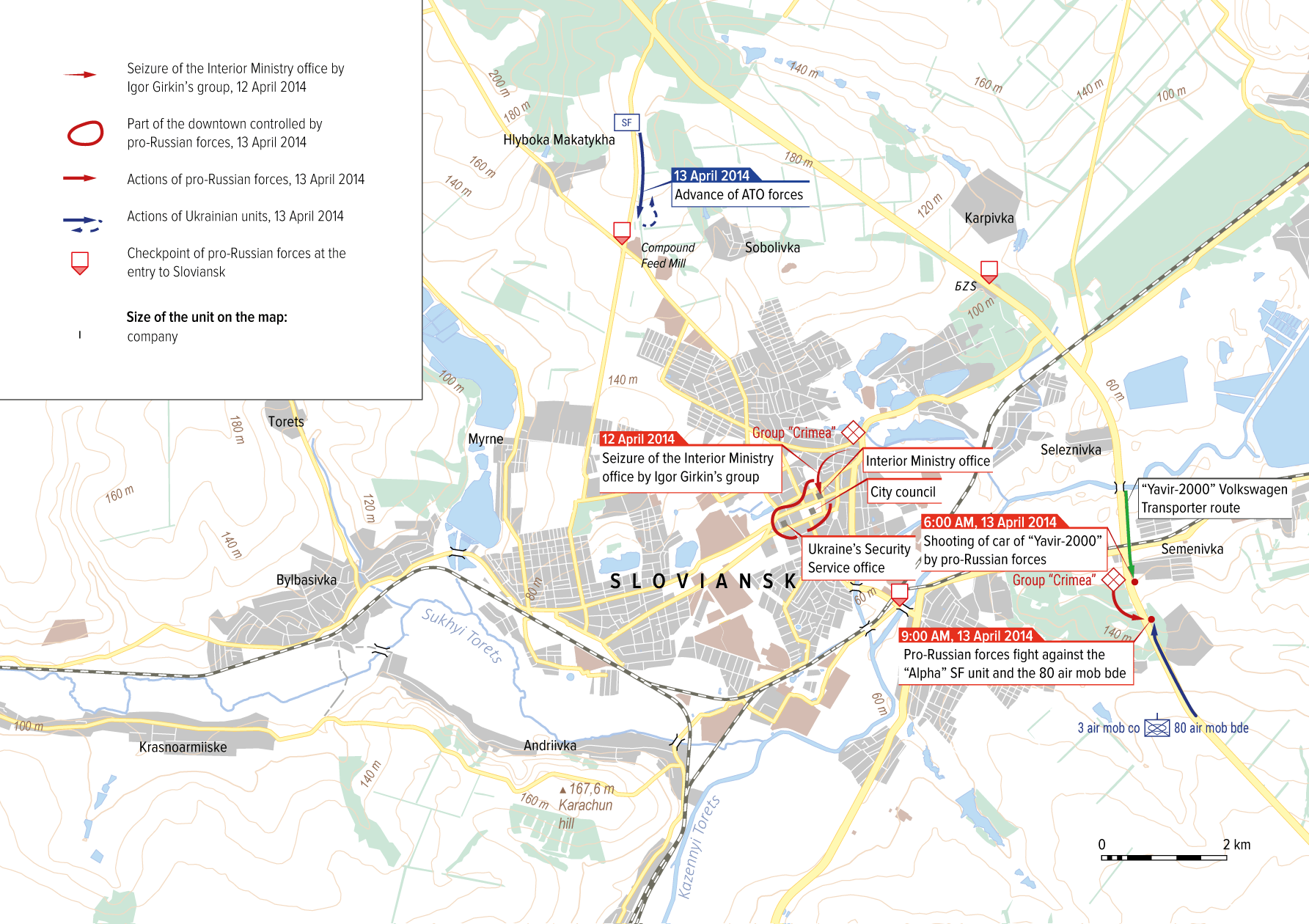

Seizure of Sloviansk

A Russian subversion group led by Igor Girkin made his first step by taking control of the city of Sloviansk in the Donetsk region. By 2014, there were more than 110,000 people living there. In spite of the Russian stock phrase of “rebel miners” that was subsequently untwisted, Sloviansk was not a mining city. There are no mines in the city; instead, it has a machine-building plant, several factories, clay mining for the local ceramic industry, and even sanatoriums, salty lakes and therapeutic mud. In 2013, just a year before the war, Sloviansk won first place on the Parade of Vyshyvankas (Ukrainian national clothes) in Kyiv: Its delegation to the capital was the best and most numerous, including more than 700 people.

Sloviansk is tactically important. It is called the “Donbas Gate” because it is located on International Highway M-03, and its blocking would cut off all the traffic from the northwest, the Kharkiv direction, to the agglomerations of industrial Donbas. The average size of the city, its important geographical location and, perhaps, its symbolic name (which originates from Slavonic) were the reasons why it had been chosen for the invasion.

On 12 April 2014, the Crimea group of 52 people, led by Igor Girkin, took the city. The group members were well-trained and equipped with automatic weapons, machine guns, sniper rifles, and grenade launchers. The group had actively acted during the Crimean events, where it had had a hand in provocations, the protection of various important persons, etc. Some of its members had also participated in the assault on the 13th Photogrammetric Centre in Simferopol on 18 March 2014, when warrant officer Serhii Kokurin was the first military serviceman of the Ukrainian Armed Forces to fall victim to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict.

At about 8-9am, the diversionists stormed the local department of the Interior Ministry, with the police not actively resisting. An hour later, the SBU office was seized. Around a hundred local pro-Russian collaborators were armed with the weapons obtained in those facilities right away, hence increasing the number of armed militants of the pro-Russian forces in the city to 150.

The situation in Sloviansk was unlike any previous unrest in Donbas. Whereas before Sloviansk administrative buildings and police station had been seized by unarmed people, who had stormed the buildings and overwhelmed their opponents by number, the case of Sloviansk was completely different: Armed men in Balaclavas seized a large city near the centre of the region and took power into their hands.

Photos were taken in the city as had been in Crimea, with people being photographed together with Girkin’s soldiers, who were thought by locals to be Russian troops because of the same uniform and weapons. However, it was not only the locals who believed this group was regular army; Ukrainian news media also called them «green men,» who had been in Crimea and now turned up in eastern Ukraine. To some extent, this was really the case: Some fighters from the streets of Sloviansk were identified in photographs taken in Crimea during the annexation, with weapons in their hands. But in terms of status, Girkin’s group was not part of the regular Russian army—this was a specially formed group of «volunteers» with combat experience, which the Russian authorities used for their own purposes.

It was not only Ukrainians who were having a strong feeling of the repeat of the Crimean scenario. Igor Girkin himself, as the field commander, and Alexander Boroday, soon to become the first «prime minister» of the newly established «DNR,» were firmly convinced that the events would be following the Crimean logic. Therefore, the full-scale deployment of Russian troops—as in Crimea—was a matter of a few days, or weeks at most.

Girkin recalled:

“When the Sloviansk saga started, I set myself to do everything as in Crimea, and the hope was that everything would be going under the Crimean scenario. That is, it was planned to help local leaders and militants to establish people’s power, hold a referendum, and accede to Russia: It was our common aim, and their aim first of all.”

Here is what Boroday wrote about it:

“And, in addition, keep in mind that Igor [Girkin], like all of us, at first expected a sprint race. [..] When I became prime minister of the DNR, I was also thinking: Well, how long will I be the prime minister—five days, a week, or even two weeks?”

If someone from the Russian authorities gave them certain guarantees and assurances, they might really have had grounds for thinking so. However, their plan failed: There was a circumstance that changed the course of events. This was the Anti-Terrorist Operation.

Anti-Terrorist Operation

An emergency meeting of the Council of National Security and Defence on the night of 12—13 April discussed the actions of the Ukrainian forces in connection with the situation in eastern Ukraine. The anti-terrorist operation was decided to begin at 9:00am on April 13th. At night, the deployment of the Ukrainian forces outside Sloviansk began, including special units of the Internal Troops, the SBU, and the Interior Ministry. The conflict had taken a new turn.

The 3rd airmobile company of the 1st battalion of the 80th separate airmobile brigade on armoured personnel carriers, led by senior lieutenant Vadym Sukharevskyi, call sign Borsuk (Badger), was deployed outside Sloviansk. The company had been sent from the Luhansk airport area, which the fighters had taken on April 8th, having marched across the whole of Ukraine from Lviv.

SBU special operation units Alpha, which were to return control over the seized building of the SBU, were sent from the Luhansk region. Because of events under the Sloviansk they were called back. It was planned that the SBU group was to be supported with armoured personnel carriers of the 80th separate airmobile brigade; armoured vehicles were also planned to be provided to the Interior Ministry special operation unit Omega under the command of Anatolii Strelchenko, which was to be transported on Mi-8 helicopters and take control over the Kramatorsk airfield. An airborne company of the 25th separate airborne brigade was also operating around Kramatorsk.

Yavir-2000

However, as the Ukrainian forces were being deployed, some seemingly strange things happened on the morning of April 13th.

On 13 April 2014, at 4:53am a group of diversionists from the Crimea group stopped a white Renault Logan, ВІ 3114 ВІ, belonging to the Yavir-2000 security firm, with two guards, who were accompanying the freight of ferroalloys being transported by rail, on the Kharkiv—Rostov-on-Don highway near Sloviansk. The militants captured the guards, took them to the basement of the SBU building in Sloviansk, and later, used the car in another operation.

The Yavir-2000 office noticed the deviation of the GPS device of the car from the course and loss of communication with the crew. At around 6:00am, a white Volkswagen Transporter, ВI 0887 ВЕ, was sent to find the stolen car. While going the route of the stolen Renault Logan, the minibus came across armed people after a railway crossing near Semenivka, a settlement outside Sloviansk. Five diversionists with assault rifles tried to stop the minibus on the highway. The driver slowed down to circumvent them, but did not stop completely and continued the drive. Immediately after that the minibus was fired, the driver was wounded five times, with one bullet hitting the spine. The second guard at the passenger seat took the driving seat and managed to bring the driver to the hospital on flat tyres.

At 7:20am, Yavir-2000 filed a report to the Sloviansk department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in connection with the abduction of the car and the disappearance of the guards.

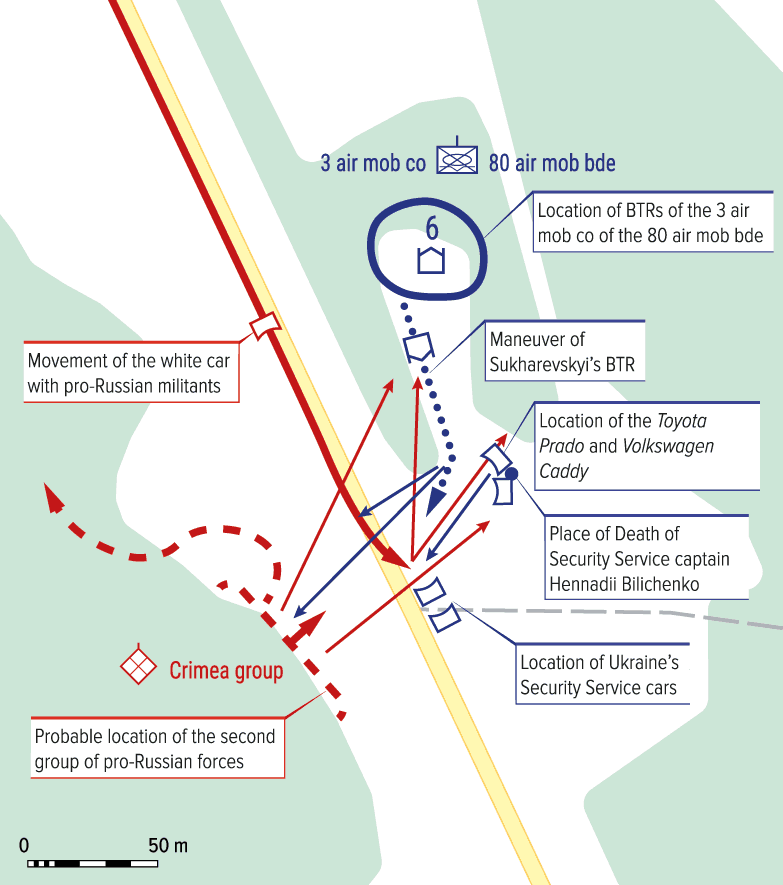

First Battle

An airmobile company deployed its armoured personnel carriers on a glade near Semenivka and set a guard. Senior SBU officers of the SBU—two deputy heads, Viktor Yahun and Vitalii Tsyhanok, and Commander of the Airmobile Troops Oleksandr Shvets—were on the glade as well. There they had been standing for some time, attracting the attention of drivers passing by. It was quite clear that the Ukrainian side was planning something—which, of course, buried any hopes for the concealment of the operation.

The mayor of Sloviansk, Nelia Shtepa, came to the officers to negotiate. After the negotiations, she left the glade. All that was recorded on camera by Volodymyr Kolodchenko, a deputy of the Mykolaiv City Council.

The Alpha group from the Poltava SBU office, including Lieutenant Colonel Andrii Dubovyk, was surveying enemy checkpoints on two cars without the support of armoured vehicles. When passing by the glade, the Alpha officers saw armoured vehicles, drove up to them and got out of the cars to coordinate their further actions.

This is when the attack happened. At least one car—the white Renault Logan belonging to the Yavir-2000 firm, which had been captured by the militants earlier in the morning—stopped at the side of the glade. Andrii Dubovyk says that there were three cars. At least four militants in camouflage got out of them and immediately started shooting to kill. Dubovyk’s account of the events and the militants’ daring actions imply that the latter were from the bulk of the Crimea group. The paratrooper Vadym Sukharevskyi and Andriy Dubovyk say that a second group of militants started to shoot from the «greenery» nearby.

The militants’ units had the following structure: Local collaborators grouped around four to six Russian diversionists, thus creating a military unit. This probably was the structure used in the fight outside Semenivka. It is likely that up to five locals were firing from the “greenery.” According to the participants of the fight, the militants firing from the «greenery» were wearing athletic costumes, bearing out such an assumption.

From the Russian side, the commander was Sergey Zhurikov, call sign Romashka (Chamomile)—the then right arm of Igor Girkin. Zhurikov was born in Crimea, was granted Russian citizenship at the age of 20, trained as a sniper and paratrooper (with 1500 jumps with a parachute), was an acolyte of Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra, and took part in the assault on the photogrammetric centre in Simferopol.

Using the surprise effect, the enemy imposed its course of combat, holding the initiative. Six fighters of the Poltava Alpha group opened fire in response. There was no help from the commanders; the distance prevented the conduct of an effective and purposeful fire from pistols.

In this situation, the Ukrainian paratroopers who were nearby quickly got into armoured personnel carriers, but did not provide supporting fire. Later, it became known that they had had orders from the command not to open fire.

The battle escalated quickly: Andrii Dubovyk was easily injured, whereas Captain Hennadii Bilichenko was fatally shot, bleeding with arms in his hands. Andrii Dubovyk recalled the battle:

“I had an RGD grenade and two stun grenades with nails. I threw them over our car—the enemy had already been there. Explosions were heard, someone screamed, I looked from behind the car, and, all of a sudden, I saw some ‘devil’ with an assault rifle right before me—and we opened fire together. It was like in a movie—albeit for a fraction of a second—as my round pierced his body and he shot at me. I was thrown up and fell near the car, having difficulty breathing.

“I heard on the radio, “Gena is dead!” I struggled to reply, “WIA. In chest.” Suddenly, someone in a mask and black Adidas sportwear jumped from behind the car. Paying no attention to me, he immediately opened fire at our other cars. I put the rifle on my thigh and shot him with the remainder of the magazine. And right after, I blacked out.”

Ukrainian special forces’ resistance was weakening fast, but, suddenly, an APC-80 of the 3rd airborne company—the only one out of six available—entered the fight. The armoured personnel carrier, led by the commander of the company, Vadym Sukharevskyi, disobeyed the order of the higher command and opened fire from a heavy machine gun at the militants, saving the Alpha fighters. The militants started shooting the APC, but without anti-APC weapons this was useless. The enemy began to retreat. Having picked up the wounded soldiers, the APC retreated, too.

Captain Hennadii Bilichenko was killed in the battle with arms in his hands. He became the first killed defender of Ukraine in the war in the East.

To date, only one killed militant has been identified. It was Ruben Avanesyan, born in 1985, from the city of Donetsk. Myroslav Rudenko, then one of the leaders of the «People’s Militia of Donbas,» explained two days after the battle that Avanesyan had died in a different way. Rudenko argued that two cars of the members of the «People’s Militia of Donbas» with humanitarian supplies and no arms were intercepted by a Right Sector car on the highway. One car, he said, was able to escape, while the other one, with Avanesyan, was shot, and Avanesyan himself, according to Rudenko, «was finished,» due to multiple gunshot injuries to his legs and stomach. These details bear a striking resemblance to the account of the fight from the Ukrainian soldiers. Therefore, it can be argued that at least two cars participated in the attack on the Ukrainian soldiers, and the nature of Avanesyan’s injuries indicates that it was he who was shot by Andri Dubovyk.

The militants abandoned the car on the roadside—the Renault Logan of the Yavir-2000 company. Inside the car, a half-conscious man in a black leather jacket and a wooly hat was found lying on the floor. Yellow Scotch tape was tied on the sleeves of his jacket. The man explained that he had been abducted that night while repairing his car on the roadside; the last thing he remembered was his having been approached from behind by someone offering help.

Russian propagandistic TV channel LifeNews described all these events in a completely distorted form. It reported that the «militia» had allegedly been on guard along with Ukrainian paratroopers when a few cars pulled off the road, and members of Right Sector got out of them and opened fire on the «militia.» Then the Ukrainian troops used an armoured personnel carrier to fend off Right Sector, and the latter retreated.

ifeNews reported that two bodies had been found in the abandoned car of the attackers—a Renault Logan of the Yavir-2000 company. The first was the body of a man “in black camouflage,” who allegedly was already numb, and therefore died «a few hours ago.» The second was a man in a leather jacket, who supposedly had to become the second victim of this provocation. In the footage with the man who had “died long ago,” shown on LifeNews, was Hennadii Bilichenko sitting in a puddle of his own blood under the SBU Toyota Prado jeep and still bleeding. This is a striking example of Russian propaganda—they managed to convey several messages in one report:

- The attackers—pro-Russian forces—were called victims

- Right Sector, which was not involved in the attack, was claimed responsible

- The argument of the alleged cooperation between the Ukrainian Armed Forces and pro-Russian militants was put forward

- The supposed malice of Right Sector was implied, since it had prepared dead bodies for provocation and was ready to execute another innocent civilian

On the same day, April 13th, another skirmish took place in Sloviansk. The militants on a car were chasing another car—a white Renault Logan—near the downtown. They were firing at the car on the move; eventually, the driver of Renault lost control, the car stopped, the driver and passengers fled in different directions, and were shot at afterwards. One of the passengers was wounded in the shoulder and captured by the militants. He was taken to the city hospital literally 50 metres from where it all happened. In the car, a permit was found in the name of Andrey Meshcheryakov, a journalist of VGTRK, a big Russian state news media.

In the hospital, Russian journalists Pavel Kanygin and Illya Azar discovered that Ruben Avanesyan had recently died of wounds. Having interviewed the staff and supposedly close friends of Ruben (a girl who claimed to be his bride did not know his surname), both journalists concluded that Ruben had been shot in that car in the middle of Sloviansk. However, now that more information is known, it can be argued that their conclusion was wrong. Avanesyan had probably been taken to the Sloviansk hospital immediately after the morning attacks on the Ukrainian forces outside Semenivka, and died there. And the journalists and the staff could have thought the two skirmished to be the same event; otherwise militants should have shot their own car, which seems unlikely. It is curious that the car of the Yavir-2000 company, which had been stolen that morning and then abandoned by the militants outside Semenivka, and the car that was shot in Sloviansk downtown were both white Renault Logans (the only difference being that the car of the Yavir-2000 company had the company’s symbol on its body). It can be assumed that, having lost a Renault Logan outside Semenivka, the militants expected that Ukrainian special operation forces would try and get into the city on that same car, and attacked a random car of the same make with Meshcheryakov.

Nothing in particular happened on that day in the other areas. The Ukrainian Interior Ministry forces mopped up the checkpoint on the other side of Sloviansk, which had previously been abandoned by the militants, but did not secure their position there and left it. Militants burned tyres at another checkpoint, with the smoke seen all over Sloviansk.

The very next day, on 14 April 2014, the SBU publicised an intercepted telephone conversation between two individuals who were then little known of—one with the callsign Strelok (Shooter) and the other being Alexander from Russia. Those were Igor Girkin and Alexander Boroday. Girkin was telling Boroday:

“… [They] suffered a lot of casualties. We do now know who we ‘chopped up,’ but it must have been someone serious. […] We need information about who we ‘chopped up.’ A very serious group was ‘chopped up,’ with some very serious people.”

In the same conversation, the record of which was publicised by the SBU on April 14th, there was an unidentified individual, of which only their telephone number was known. The voice of this person who spoke with of Girkin belongs to Konstantin Malofeev, which is easy to check by comparing it with any of his public speeches. In 2015, Malofeev would call this record a «fake,» although there are no grounds for doubting its authenticity.

Girkin: “They got into our ambush. Our group shot three VIP cars in which they were moving […] Konstantin Valeryevich [Malofeev], I ask you to specify who we actually beat up. We have conflicting information here, ranging from Alpha fighters to Ukraine’s Military Intelligence special forces.”

Malofeev: “I can officially confirm that you wounded the head of Ukraine’s Anti-Terrorist Centre. So you shot just the right person.”

Girkin: “Great. Thank you.”

Malofeev: “Alright, good luck to you. I would also like to say that you celebrated the holiday well.”

Girkin: “I did my best! Thank you!” [Both laugh.]

On 13 April 2014, Palm Sunday was celebrated in Ukraine.

Russian Narrative

Russia’s coverage of the events in Sloviansk was meant to confirm the picture long advanced by Russia: That the Armed Forces of Ukraine were supposedly on the side of the “insurgent people of Donbas,” and only the insidious Right Sector wanted to fuel the war between the fraternal peoples.

In 2016, Girkin gave an interview to online media outlet Ukraina.ru, describing his first days in Sloviansk. In the interview, he either deliberately lied or, due to being inattentive, confused the timeline and made up some events, shifting responsibility for the first blood on the Ukrainian side:

“There still was an opportunity to disarm the columns. Outside Sloviansk, on the bridge between Sloviansk and Karachun, a column of 11 armoured carriers was blocked, and it, of course, could have been destroyed. But I realised that the blood would be shed—we would have to kill the fighters, including the conscripts, and burn the armoured carriers… They could not have been disarmed without fight. And they outnumbered my entire garrison at the time. They would have seen this and would not have given up their arms without fight. So they just killed a few civilians and passed.

“Everyone—I, my fighters, and even Ukrainian soldiers (at least many Ukrainian officers who were aloof from Maidan propaganda and all that craziness)—everyone hoped that Russian troops would come, and we would not have to fight. But this never happened. If it had been clear beforehand that Russian would not give any help—well, we would have acted differently then. And so we acted as we acted…

“In any case, the first blood was shed by the enemy—at Easter, Right Sector fighters attacked the checkpoint and killed two militants. Later, Alpha intelligence officers met with my intelligence officers near Semenivka on April 16th. So they were the first to take military action.”

The sources available in 2019 do not confirm any fact of the death of civilians allegedly killed by Ukrainian troops for unblocking the column. Therefore, claims about the death of civilians should be considered false and perceived as misinformation until there are facts to support those allegations. Girkin also confused the timeline of the events: The battle with Alpha officers outside Semenivka took place on the morning of April 13th, not April 16th, as he claimed. The fight with Right Sector at the checkpoint near Bylbasivka took place on 20 April 2014, at Easter. That the direct participant of those events and the commander mixed up the order of those two events, which took place a week from each other due to being inattentive, seems unlikely. Hence, this is either Girkin’s purposeful lie or the criminal’s subconscious desire to whitewash himself.

Afterword

In 2014, Oleksandr Khodakovskyi, the commander of the Donetsk Alpha group, who sided with the Russian side in 2014, said of Girkin’s invasion:

“When he entered Sloviansk, he had some assurances; he has some plans, promises… I think, and everything indicates this, that he entered with the only aim in mind: To create a situation, a real pretext for Russian army to enter as well.”

The actions of Girkin’s group did look like a provocation—a provocation which in the early days had to lead to dozens of civilian casualties because of the use of force by the Ukrainian army. It probably was to have been a pretext for the invasion of Russian troops (perhaps under the guise of peacekeepers).

On 16 April 2014, the head of the SBU counterintelligence unit, Vitalii Naida, said that Russia was ready to play out this scenario:

“The country that claimed it was a fraternal one is tasking its special operation forces with shedding blood in the streets of our cities. We have records of intercepted talks discussing that 100 to 200 people have to be killed so that in an hour and a half, tanks and BTRs of the Russian army will appear in Ukrainian territory.”

Russia was directly interested in creating a “hot spot” in Ukraine. The Kremlin had already realised that it would be impossible to sway all eight southeastern regions of Ukraine, but even a local conflict within Donbas could be taken advantage of by the Russian authorities–either to pressurise the Ukrainian government or as a bargaining chip in the negotiations on the recognition of Crimean annexation.

But nothing “explosive” happened at the initial stage of the war: The events were gaining momentum gradually, without large-scale incidents, with the sides acting cautiously. The Ukrainian army was not going to give a pretext for the full-scale invasion of Russian troops, whereas militants under Girkin’s command did not have enough strength to move beyond the city.

In an interview to BBC correspondent Yuri Vendik about the early events of the war, Konstantin Malofeev said of the status of Ukrainian forces:

“…The legitimacy of both Girkin’s and Bezler’s groups and what you call the National Guard was the same. These were armed groups opposing each other.

“The former fought for the “Russian World,” the latter for “Glory to Ukraine”; but both, in legal terms, were armed groups of people with no powers.”

Speaking about the war in Donbas, Malofeev shows complete ignorance, be it false or sincere. In the interview, he also said that the newly formed volunteer battalions of the National Guard had been nothing more than gangs because they had been created from novices pursuant to the allegedly illegal decision of the Verkhovna Rada. Even putting aside the absurdity of the inferences about the status of National Guard volunteer battalions, the facts indicate quite the opposite: The first battle in the war involved only Ukraine’s regular force units from different institutions—regular troops of the 80th brigade of the Armed Forces; fighters of the Poltava SBU office; and special forces of the Omega group. Ukrainian volunteer fighters would play an important role in fending off Russian aggression, but the regular Ukrainian military units were the first to stand up against the invasion.

Read also:

- Ukraine’s Armed Forces on the Eve of the Conflict

- Springtime for the Invader, Part One

- Springtime for the Invader, Part 2

The contents of the article are licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. Copyright exceptions are marked with ©.

The article was prepared with the assistance of the Ministry of Information Policy of Ukraine.

SUPPORT MILITARNYI

Even a single donation or a $1 subscription will help us contnue working and developing. Fund independent military media and have access to credible information.

Vadim Kushnikov

Vadim Kushnikov

Андрій Тарасенко

Андрій Тарасенко

Юрій Юзич

Юрій Юзич

Віктор Шолудько

Віктор Шолудько

Роман Приходько

Роман Приходько

Андрій Харук

Андрій Харук

Yann

Yann

СПЖ "Водограй"

СПЖ "Водограй"

ГО "Військова школа "Боривітер"

ГО "Військова школа "Боривітер"