The Problem of War crimes vs European integration of the Western Balkans, part 2

The original article was published on the Balkans in-site. Any reprints of the article only with the permission of the author and the Balkans in-site.

The foreign policy of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Northern Macedonia focuses on European integration. But the mentioned countries have several internal and external problems, so their accession to the EU is in great question. In particular, this is the problem of war crimes, which remains a cornerstone of B&H-Kosovo relations with the EU. Such a problem has never existed for Northern Macedonia.

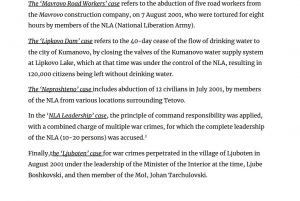

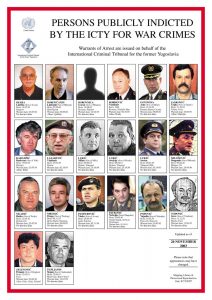

The Northern Macedonia government, unlike other republics in the former Yugoslav federation, never resisted the work of ICTY investigators and prosecutors. The tribunal has five jurisdictions that are classified as war crimes. ICTY Prosecutor’s Office has transferred four cases of ‘Mavrovo Road Workers’, ‘NLA Leadership’, ‘Neproshteno’ and ‘Lipkovo Dam’ from the Hague to the Prosecutor’s Office of Northern Macedonia. Cases at the local level have either been suspended or frozen. The ICTY has dealt with only one case involving crimes committed by Macedonian security forces and police in the village of Luboten, near Skopje. In The Hague, only Johanna Tarculowski, who commanded one of the police units that committed war crimes in Luboten, was brought to justice. Another accused, Lube Boskoski, was acquitted.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the process of convicting persons suspected or accused of war crimes has lasted more than two decades. It is due to several factors. First, the country has created a very complex state structure under the Dayton Peace Accords, which has paralyzed all authorities and institutions. Because of this, for a long time, there was no specialized structure in Bosnia and Herzegovina that dealt exclusively with war crimes. Only in 2005 was the War Crimes Division of the State Court, which was to operate as a state specialized institution permanently in Sarajevo.

Secondly, for the population of each of the entities of B&H, the concept of war criminals is blurred. This category usually includes soldiers of enemy armies, not their soldiers or generals. For them, they are national heroes who defended the Motherland. Due to this, the ICTY trials were delayed and the defendants were sentenced. For example, former Republika Srpska President Radovan Karadzic and former Republika Srpska Army General Ratko Mladic refused to be handed over to the ICTY by the Republika Srpska entity. The arrest of Karadzic in 2008 and Mladic in 2011 unblocked Bosnia and Herzegovina’s negotiations with the EU on European integration.

Third, the country still lacks an effective judicial system to deal with war criminals at the local level. The OSCE has consistently noted in its reports that the number of cases opened against war crimes indictees in Bosnia and Herzegovina is steadily declining. The situation is similar with the consideration of already opened cases. Trials are postponed, delayed, or canceled due to various circumstances. First of all, this is caused by the lack of testimony and witnesses, information fragmentary, and the reluctance of people to bring charges against their perpetrators.

A characteristic feature work of the War Crimes Division of the B&H State Court is the prosecution of only Bosnian Serbs and Bosnian Croats. Cases against Bosniaks are rare. The same trend has been in the courts dealing with war crimes cases in Serbia, Croatia, Montenegro, and Kosovo. The consequence of such actions is one-sided processes and deteriorating relations between countries.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the situation is complicated by the Republika Srpska authorities’ refusal to cooperate with the Muslim-Croat Federation (another entity within B&H) to comply with orders from the EU High Representative and to recognize the involvement of Bosnian Serbs in war crimes committed by prosecutors.

In 2020, B&H has adopted a State Strategy for War Crimes. It is the second such document in Bosnia and Herzegovina to establish state control over bringing persons who were involved in war crimes in 1992-1995. The previous strategy was approved in 2008 and was due to run until 2015 to complete all war crimes cases. However, the document proved ineffective, and Bosnia failed to come close to resolving one of the key obstacles to the EU.

The new strategy, according to senior officials, should speed up the process. Some experts think the State Strategy for War Crimes (2020) will allow all cases to be considered by 2023 and close to the country. At present, this seems impossible, as some cases related to war crimes and criminals were initiated in 2019-2021.

In 2019, according to the OSCE Mission to B&H, 49 cases were considered, in 2020 this figure dropped to 18. It is explained not only by problems within the country but also by the impact of the coronavirus pandemic. Due to quarantine, the trials of defendants in war crimes cases were postponed. As of July 2021, the B&H Prosecutor’s Office had filed only six war crimes charges.

Thus, the OSCE figures once again prove B&H’s lack of interest in finally resolving the problem of war crimes and starting a new phase of accession talks with the EU. The number of such cases decreases so it demonstrates that the State War Crimes Strategy (2008 and 2020) ineffectiveness, as the transitional justice process initiated in the countries of the former Yugoslavia with the assistance of the EU. In B&H, as in other post-Yugoslav states, it is run only by non-governmental organizations. The authorities have nothing to do with transitional justice, which creates additional obstacles for B&H, Serbia, Montenegro, and Kosovo in the EU accession dialogue process.

References:

- Тужилаштво Босне и Херцеговине http://www.tuzilastvobih.gov.ba/?opcija=sadrzaj&kat=2&id=4&jezik=s

- Grebo L. (2021) Bosnia Completing Fewer War Crimes Cases, OSCE Warns (2021, August 11), BalkanInsight. https://balkaninsight.com/2021/08/11/bosnia-completing-fewer-war-crimes-cases-osce-warns/

- REVIDIRANA DRŽAVNA STRATEGIJA ZA RAD NA PREDMETIMA RATNIH ZLOČINA (2018). Sarajevo, maj 2018. godine, 30 str. http://www.mpr.gov.ba/web_dokumenti/default.aspx?id=10809&langTag=bs-BA

- Usvojena Revidirana državna strategija za rad na predmetima ratnih zločina (2020), Ministarstvo pravde Bosne i Herzegovine (2020, 24.09). http://www.mpr.gov.ba/aktuelnosti/vijesti/default.aspx?id=10793&langTag=bs-BA

- Volchevska B., Zdravkova I. (2020) How North Macedonia Traded Justice for Peace (2020, December 24), BalkanInsight. https://balkaninsight.com/2020/12/24/how-north-macedonia-traded-justice-for-peace/.

- BOŠKOSKI & TARČULOVSKI (IT-04-82), Case Information Sheet, ICTY, 5 p. https://www.icty.org/x/cases/boskoski_tarculovski/cis/en/cis_boskoski_tarculovski_en.pdf

#EU #war_crimes #WesternBalkans #NorthMacedonia #BiH

SUPPORT MILITARNYI

Even a single donation or a $1 subscription will help us contnue working and developing. Fund independent military media and have access to credible information.

Роман Приходько

Роман Приходько

Віктор Шолудько

Віктор Шолудько

Андрій Харук

Андрій Харук

Андрій Тарасенко

Андрій Тарасенко

Yann

Yann

СПЖ "Водограй"

СПЖ "Водограй"

ГО "Військова школа "Боривітер"

ГО "Військова школа "Боривітер"

Катерина Шимкевич

Катерина Шимкевич

Олександр Солонько

Олександр Солонько

Андрій Риженко

Андрій Риженко